A terraced campus design inspired by historic stepwells

Situated within a 13-ha (32-acre) university campus, the main administration offices, along with an auditorium, seminar halls, library, and cafeteria, form the functions of Prestige University’s campus building in Indore, India.

Stepped up diagonally from the northern point, the entire terrace of the five-level building is accessible to the university’s students and faculty, transforming it into an open auditorium.

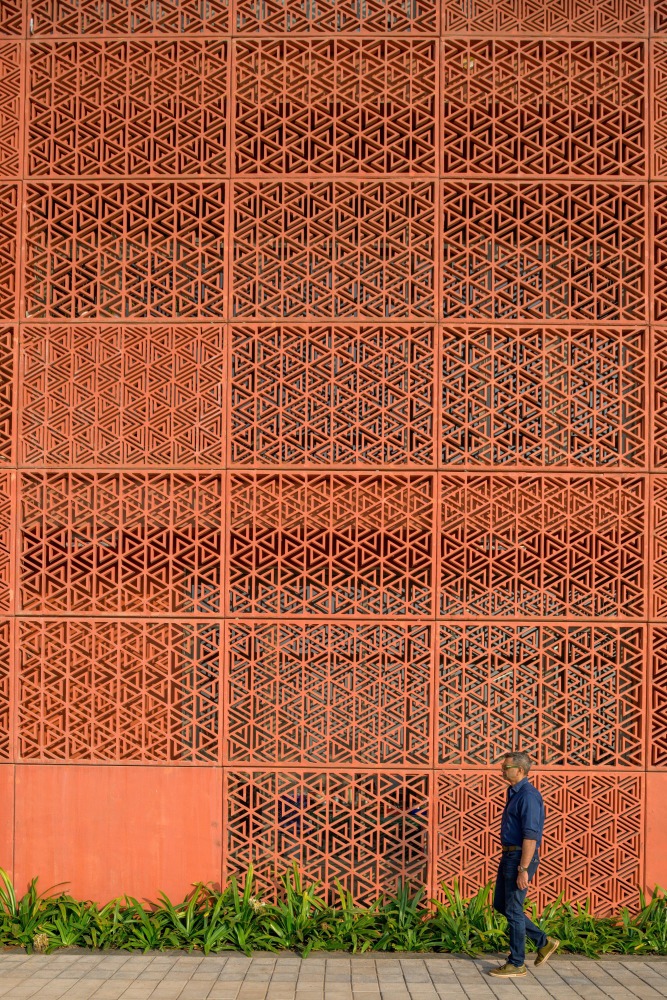

The north lighting and courtyards are imbued with traditional Indian architecture, creating an energy-efficient, sustainable building with minimal dependence on artificial lighting and air conditioning.

The built form evokes images of stepped wells, which have existed in India for 1,100 years and served not only as water storage but also as spaces for large-scale social interaction.

A total of 463 stepped platforms form a 9,000-m2 (96,875-sf) rooftop garden.

The common facilities, including a food court, an auditorium, and the administrative offices, are located on the ground floor for easy access. The various library components are located on the first floor and are connected by a bridge over the diagonal indoor street that cuts across the building. The common classrooms occupy the second floor, deriving light and ventilation from the various sectional volumes and open courts. These open courts serve as overflow areas for recreational activities. The third floor houses tiered classrooms, and the fourth floor houses all administrative and faculty facilities.

Sanjay Puri Architects was behind the architecture and interior design of this project.