Bringing acoustics to hardware: The science behind low-noise design

Increasingly, building projects are not only concerned with requirements such as safety and energy efficiency, but also occupant comfort. One aspect of this is noise. Noise from HVAC units, noise from other work areas, and noise from door hardware. How many times has a person’s concentration been disrupted at a meeting or conference by someone entering or exiting the room? It is essential to specify door hardware for those areas of the building that require an additional level of quiet. The Builders Hardware Manufacturers Association (BHMA) has undertaken the task of determining door hardware suitable for quiet environments with its new standard, ANSI/BHMA A156.42, Acoustic Performance Rating for Operational Noise of Architectural Hardware.

BHMA is the trade association for North American manufacturers of commercial builders’ hardware. The organization is involved in standards, codes, life-safety regulations, and other activities that influence performance requirements for products such as locks, closers, exit devices, and related components. BHMA is the only organization accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) to develop and maintain performance standards for locks, closers, exit devices, and other builders’ hardware. BHMA currently has more than 40 ANSI/BHMA standards. The widely known ANSI/BHMA A156 series of standards sets performance criteria for an array of products, including locks, closers, exit devices, butts, hinges, power-operated doors, and access control products.

With A156.42, BHMA is once again looking to stay abreast of market needs. There are studies detailing the effects of extraneous noise in various environments. The studies show many factors contribute to the issue. The BHMA member companies have decided to address this problem and ensure that their products are part of the solution. But the concept of “quiet” is not easily quantifiable and varies considerably for different applications. In a medical environment, acceptable noise levels differ significantly from those in a conference room.

The development of the standard took a total of six years. A significant factor during this time frame was the lack of acoustical measurement expertise within the BHMA membership. So, forming a strong partnership with a sound laboratory was essential.

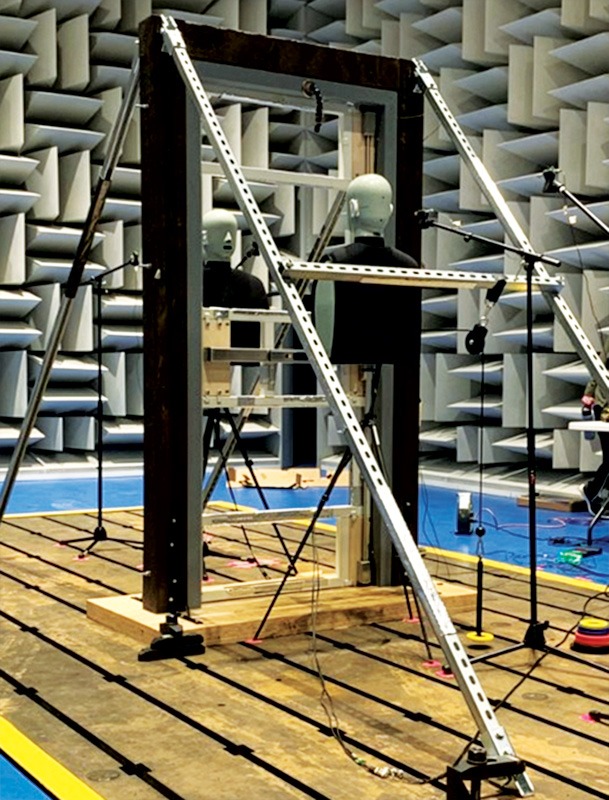

First on the list of developments was a test fixture. Above all, it had to be acoustically dead. Noise from external elements can be hard to remove from recordings and will impact the product’s sound. Additionally, it had to be able to accommodate a wide variety of products and facilitate quick changeovers. After several iterations, a fixture was developed to meet this criterion; in testing, it did not add any extraneous noise to the recording.

Next, a testing procedure needed to be developed. The cadence established is a combination of real-world usage and limitations on recording. The real-world aspect was determined by averaging field measurements, such as the speed at which a bar is pushed and released, the rate at which a lever is turned, and the rate at which a door closes. Recording restrictions are necessary not only because of the large file sizes, but also because long recordings make it more difficult to identify specific areas of concern.

The testing cadence is broken up into three main activities:

- Door opening—Actuation of the product and opening the door (e.g. turning a lever or pushing a bar).

- Product release—With the door in a fixed open position, the actuation point of the product is released (e.g. letting go of a lever or bar).

- Door closing—A weight system pulls the door closed at a fixed speed, allowing the product to latch.

These three activities define typical door operation, allowing manufacturers to focus on areas for improvement. When aspects, such as pushbar actuation versus release, are evaluated separately and receive their own score, it helps the manufacturer determine where to allocate design effort. Further, each activity is monitored for execution speed, which includes avoiding excessive pushing or turning, as well as measuring the total time taken to complete the activity. If any of these parameters fall outside specified values, the recording is rejected, and a new one is taken. All actuations are performed by human hands. The lab has experience with this and found that non-human actuation introduces noise.

Lastly, products were needed to test. With multiple door hardware companies participating, a wide range of products was tested to achieve not only a broad application range but also a diverse sound range. Once the “what,” “where,” and “how” were determined, the recording process began. Testing was conducted in a semi-anechoic sound chamber, with the fixture and testing procedure in place. There were 10 recordings made for each activity, each two seconds long.

Once the recordings were finished, an analysis of the recordings began. At first, a simple analysis was considered using Peak Instantaneous Loudness. It was quick and understandable, but too general to decide what a quiet device was. Even when products deemed quiet were tested, it was not possible to distinguish them from other products. Due to the lack of clear product delineation, the BHMA team and testing laboratory personnel concluded that this analysis was inconclusive.

The subsequent phase involved evaluating the recordings by a sound jury. A sound jury is comprised of a group of impartial individuals who assess a variety of sounds, rating each based on how it might be perceived in a quiet setting. In this study, a total of 53 jurors from diverse demographics participated in sessions lasting 45 minutes. Each participant engaged in four paired comparison tests and one semantic differential test.

During the paired comparison test, jurors listened to two sample sounds and indicated which one they found to be less disruptive. Following this, participants ranked the sounds on scales that represented opposing extremes, such as “annoying” and “pleasant,” during the semantic differential test. The sounds from the three activities were interspersed throughout the evaluation process, yielding valuable insights into the results of the paired comparisons.

From an analysis of the sound jury’s preferences of the recorded sounds, a characteristic curve was created for each of the three activities. The curve is defined by taking sounds from an activity and ranking them from least disturbing to most. This curve, then, can be used to conduct a correlation study to compare which sound quality metrics correlate most strongly. The sound quality metrics, such as amplitude, roughness, tonality, and modulation, are the computed objective parameters for each sound. There are more than 30 metrics available for comparison. Once the top two or three best-fitting metrics have been identified, a regression equation is created. Using this equation, BHMA estimated a sound’s position on the jury’s original characteristic curve. This helps quantify whether a door hardware sound from a specific action is considered more or less perceptually intrusive.

The regression equations are key to answering the question, “What is quiet door hardware?” The backbone of the equations is based on end-user preferences and is further strengthened by solid sound quality metrics. This gives confidence that products meeting A156.42 are the best choice for noise-sensitive environments that need an extra level of quiet.

To come full circle, the same products that were deemed “inconclusive” in the loudness analysis were re-analyzed with the regression equations, and quiet products were discernible from their counterparts. Since then, there has been a solid division, which led to the creation of a numerical threshold in the standard. Products that score above this threshold in each of the three activities are considered appropriate for use in a quiet environment.

As with all BHMA standards, products that are certified to A156.42 are listed in the BHMA Certified Product Directory. On the landing page, select A156.42 as the standard, and a list of products with manufacturers’ names and model numbers will be displayed. Additionally, each product certified to A156.42 must also pass certification for its mechanical standard; however, it does not replace mechanical requirements. The mechanical standard and grade level will be part of the A156.42 listing. It is crucial for the specified product to meet additional code criteria.

Author

Tony Gambrall serves as the Builders Hardware Manufacturers Association (BHMA) director of standards. He coordinates the development and revision of the BHMA performance standards for building hardware products. He came to BHMA following a career in door hardware manufacturing, focusing on the areas of product testing and development. During this time, Gambrall was also a BHMA member participating in and chairing the development of standards. He can be reached at agambrall@kellencompnay.com.

Key Takeaways

The new ANSI/BHMA A156.42 standard provides a measurable method for evaluating quiet door hardware, using specialized fixtures, human-actuated testing, and sound-jury analysis. Regression-based thresholds now define what qualifies as “quiet,” and certified products must also meet their mechanical standards, giving designers clearer guidance for noise-sensitive environments.