Enhancing community safety: Effective wildfire mitigation and building practices

In recent years, wildfire incidents such as the Camp (2018), Eaton (2025), Palisades (2025), and Tubbs Fires (2017) in California, which are collectively the four most destructive fires in the state’s history, have tragically claimed lives and destroyed thousands of structures.1 Similarly, the Panhandle Wildfires (2024) in Texas (the largest in the state’s history)2 and the Marshall Fire (2021) in Colorado (the costliest in the state’s history)3 have also caused significant devastation.

The expansion of Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) areas, which are at greater risk for catastrophic wildfires, combined with more frequent extreme weather conditions, has amplified the impact of these incidents.4 The response to, and recovery from, these increasingly complex wildfire events have strained budgets, disrupted economies, and affected countless individuals and communities. Mitigating these risks requires a multifaceted approach, focusing on both community and individual home hardening efforts. Research indicates that measures such as home hardening could reduce wildfire losses by up to 75 percent, potentially lowering insurance premiums by up to 55 percent.5

The escalating threat of wildfires

Over the past three decades, the WUI areas have experienced rapid expansion across the United States, significantly increasing the risks associated with wildfire incidents. By 2018, nearly one-third of the U.S. population lived in WUI zones, placing their homes in harm’s way. This substantial growth encompasses an estimated 70,000 communities and 46 million residential buildings, collectively valued at approximately $1.3 trillion.6

The intensified threat posed by wildfires is particularly evident in California. Since 2015, seven of the 10 most destructive wildfires in the state’s history have occurred, resulting in the destruction of nearly 50,000 structures, and since 2017, nine of the largest wildfires have burned through nearly 2 million ha (5 million acres).7 To put this into perspective, the area affected by these nine large wildfires is roughly equivalent to the combined size of Connecticut and Delaware.

The hidden health hazards of wildfires

Beyond the devastating loss of life and personal and economic impacts measured in billions of dollars, wildfires also pose significant environmental and health risks to affected communities.

Wildfire smoke contains a variety of hazardous air pollutants, including gaseous pollutants such as carbon monoxide, hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) like aromatic hydrocarbons, ozone and lead, as well as particle pollution such as fine particulate matter (PM2.5).8 Additionally, the combustion of structures further contributes to the release of myriad harmful chemicals and particulate contaminants into the air, water, and the surrounding ecosystem. This occurs because materials commonly found in the built environment, such as plastics, certain types of insulation, chemical treatments, and electronic devices, produce a range of toxic substances when burned.

These toxicants pose both acute and long-term health risks to humans through multiple exposure pathways, including inhalation, ingestion, and dermal absorption.9 Inhalation of smoke and airborne particles can lead to respiratory issues, cardiovascular problems, and other serious health conditions. These risks are particularly severe for first responders and individuals involved in wildfire cleanup.10 Contaminants can also infiltrate water supplies, leading to potential ingestion of hazardous substances. Further, skin contact with contaminated materials can result in dermatological conditions and systemic toxicity. The long-term health implications of exposure to these toxicants are still being studied, but they raise concerns about chronic illnesses and the overall well-being of populations residing in or near affected areas.11

Lastly, wildfires contribute to climate change by emitting large quantities of CO2 and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, thereby exacerbating global warming.

Beyond minimum standards

To mitigate damage from the exponential increase in the number of lost structures that is directly attributed to the growth of WUI zones and the increasing complexity of wildfire events,12 it is essential to carefully plan the arrangement and placement of structures and vegetation, as well as consider building and infrastructure design. The materials used in construction, the design of homes, and the surrounding landscaping all play a significant role in determining a home’s likelihood of surviving a wildfire; an effective strategy must include reducing available fuel loads to minimize fire spread.

California is a national leader in addressing wildfire impacts on the built environment through its comprehensive statewide building code and property-level vegetation requirements. Applicable to all new developments located in State Responsibility Areas (SRAs), and the highest fire severity zones in Local Responsibility Areas (LRAs), the 2022 California Code of Regulations, Title 24, California Building Standards Code, Part 2, California Building Code, Chapter 7A (Chapter 7A) and the future 2025 California Wildland-Urban Interface Code (CWUIC),13 are intended to reduce the vulnerability of homes to wildfire.

However, given the magnitude of California’s wildfire risks and the increasing home development in wildfire-prone areas,14 it is crucial for design professionals, builders, trade contractors, homeowners, property owners, and policymakers to recognize the option to exceed the minimum standards established by local codes and regulations. Taking measures beyond basic requirements can include using noncombustible materials and implementing comprehensive landscaping plans that prioritize fire resistance.

Exceeding these standards, specifically those of Chapter 7A and the 2025 CWUIC, may be necessary and undoubtedly beneficial. These actions will enhance the safety of individual properties and contribute to the collective wildfire resilience of entire communities.

Strategies for resilience

Given that few places are entirely free from wildfire risk, it is fundamental for communities and legislators to prioritize enhancing community resilience to effectively address and mitigate these threats.

Recognizing the importance of a unified understanding of “resilience,”15 50 organizations across various sectors, including planning, design, construction, ownership, operations, regulation, and insurance have adopted the definition proposed by the National Academies in their 2012 Consensus Study Report, “Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative”:16

The ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events.

This shared definition underscores the urgent need for comprehensive hazard assessments and robust mitigation strategies. By strengthening both structures and landscapes, communities can better protect themselves against the dangers posed by embers and wildfires.

Best practices for fire mitigation in WUI areas include the following:

- Defensible space—Establishing a buffer zone between a building and its surrounding vegetation (fuel) to decrease the risk of home ignition and assist firefighting efforts. This barrier also slows or halts the progress of fire, ensuring the safety of firefighters defending the property.

- Building and maintenance codes—Enforcing codes that mandate ignition-resistant construction for various structural components, including but not limited to exterior walls, roofs, glazing, and doors. These measures significantly enhance the fire resistance of buildings, ensuring greater protection against wildfire hazards.

- Fuel mapping and condition testing—Performing detailed fuel mapping and condition testing to assist fire behaviorists in identifying high-risk areas.17 This involves analyzing the type, quantity, and distribution of combustible materials, such as vegetation, building materials, and other potential fuel sources. By understanding the characteristics and extent of available fuel, fire behaviorists can better predict fire behavior and develop targeted strategies for wildfire mitigation.

- Assessing current capability—Conducting a thorough evaluation of existing fire mitigation strategies to determine their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. This includes reviewing physical fire barriers, defensible space creation, building materials, and community preparedness plans. Implementing these proven strategies will enhance overall fire preparedness and response, ensuring communities are better equipped to handle wildfire events.

To illustrate the importance of these practices, it is worth noting the considerable discussion about the need for defensible space between structures in the aftermath of the 2025 Los Angeles fires.18 However, this approach is often not feasible in California, given the existing housing crisis. This crisis has led to densely populated areas with limited available land, making it challenging to create the necessary buffer zones around structures.

As a result, alternative strategies must be considered to enhance wildfire resilience in such contexts, emphasizing the importance of individual home hardening efforts. By focusing on fortifying homes against fire hazards, communities can enhance their overall resilience despite the challenges posed by limited spatial separation.17

The role of embers and firebrands

Structure losses are often attributed to exposures from fire (radiation and/or convection), embers and firebrands, which are significant sources of ignition. Embers, which are small, glowing particles of burning material, can become trapped in the cracks of walls, window openings, roof vents, and door trim boards, igniting combustible materials. Firebrands, which are larger pieces of burning debris, can ignite wall coverings or roofing materials.

Findings from a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) case study of the California 2018 Camp Fire identified significant ember exposure as a primary factor in fire spread. As stated in the case study:19

In agreement with the other NIST case studies of WUI fires, the Camp Fire has demonstrated that embers can have significant impact on WUI communities. Laboratory and field work by NIST [57] has demonstrated that embers with enough energy to cause ignitions are readily generated from parcel-level combustibles such as landscaping mulch, fences, and firewood piles. These parcel-level fuels can cause ignitions over 40 m (130 ft) downwind. Ember ignitions downwind from parcel-level combustibles enable fire to readily spread from parcel to parcel. In high hazard areas, WUI structures therefore need to be able to withstand the exposures generated from both wildland and parcel-level combustibles.

Fire resistance of exterior walls

Exterior walls of residential buildings are particularly vulnerable to wildfire flames, conductive heat, and radiant heat, all of which have the potential to ignite combustible materials installed on or within these structures. Their fire performance is significantly influenced by the type of construction materials used and the proximity of external fuel sources, such as vegetation and other potential ignition sources.20

According to WUI codes, such as the 2024 International Wildland Urban Interface Code (2024 IWUIC) or Chapter 7A, certain common combustible building materials used in exterior wall coverings of residential buildings can be used in constructions classified as Class 1, 2, and 3 ignition-resistant (IR) constructions.21 However, despite these classifications, these materials can still readily become sources of fuel for an ambient fire. This is particularly concerning because materials such as wood, vinyl, and other typical exterior wall components, while potentially offering some degree of fire resistance when used in specific combinations, are still combustible. These materials can ignite, especially under extreme wildfire conditions, and contribute to the spread of the fire.22 By selecting highly ignition-resistant materials, such as noncombustible materials,23 and ensuring structures maintain a safe distance from potential external fuel sources, the overall resilience of residential buildings in wildfire-prone areas can be significantly enhanced.

It is also necessary to evaluate the ability of an exterior wall assembly to resist fire penetration from exterior fire exposure. In California, this evaluation can be conducted using the test described in the State Fire Marshal (SFM) Standard 12-7A-1,24 which is mandated in jurisdictions referencing Chapter 7A. This test specifically addresses direct flame penetration through residential exterior wall assemblies in WUI areas. However, it does not consider flame propagation along the exterior wall into attics through eaves, or the subsequent risk of spreading to the building’s interior by these paths. For this reason, using noncombustible materials in the exterior building envelope is highly beneficial, as it significantly improves a structure’s resistance to both flame propagation along, and flame penetration through exterior wall and roof coverings.

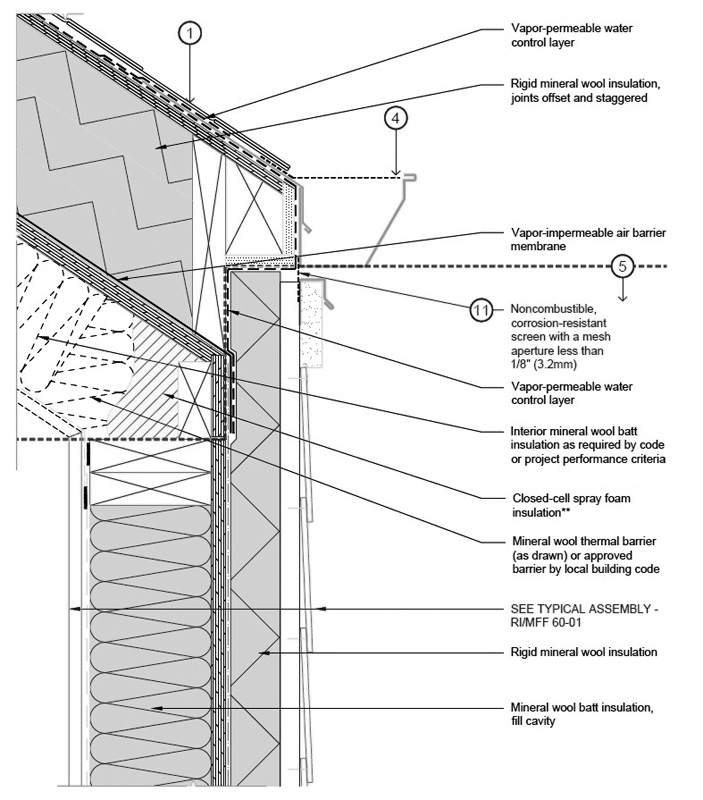

When combined with noncombustible cavity and continuous exterior mineral wool insulation,25 exterior wall coverings such as fiber-cement panels or siding, Portland cement-based stucco, masonry, stone, and metal can all be highly effective in improving fire resistance. An exterior insulation finish system (EIFS) that uses noncombustible mineral wool insulation board as a substrate, a very common type of cladding in Europe, can likewise provide increased fire protection compared to systems that use foam plastic board as a substrate,26 which are much more susceptible to flame spread and flame penetration and can add considerable additional fuel load to an ambient fire.

Flame spread on exterior surfaces of combustible materials risks fire spreading to other parts of buildings. A post-fire analysis of the Camp Fire, as discussed in the 2022 report by Headwaters Economics and the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) titled “Construction Costs for a Wildfire-Resistant Home: California Edition,”27 revealed the survivability of homes was closely linked to the proximity of destroyed structures and the density of development. The primary factors influencing a home’s survival included exposure to radiant heat from nearby burning structures and flame contact from combustible materials close to the home. This indicates homes should be designed and maintained to reduce direct flame contact, resist ember ignition, and withstand prolonged exposure to radiant heat.

Another standard test method for reducing wildfire risk to residential structures that addresses the response of materials, products, or assemblies to heat and flame is the fire resistance rating of exterior walls in accordance with ASTM E119 (or UL 263), as referenced, for instance, in the 2024 IWUIC and Chapter 7A.28 The use of fire-resistance rated assemblies helps minimize the risk of an exterior fire igniting building contents, or an interior structure fire igniting exterior vegetation and adjacent structures via direct flame impingement or radiation. The rated assemblies also provide crucial extra time for firefighting and rescue operations.

Exterior wall assemblies are typically asymmetrical. According to the ASTM E119 standard, asymmetrical walls must be tested from both sides. This necessitates standard fire resistance testing to be conducted from both the interior and exterior sides. Despite this requirement in the test standard, it is common practice to test asymmetrical walls without the outboard insulation and wall coverings, effectively rendering them symmetrical and allowing testing from a single side without incorporating combustible exterior wall claddings or combustible outboard insulations. This approach can save time and money during testing and offer greater design flexibility in choosing exterior finishes; however, it fails to assess the potential impact of additional fuel loads mounted over fire-resistance-rated walls. Therefore, while testing without the exterior finish is often accepted, it should not be considered best practice.

Including the exterior finish in testing provides a more representative evaluation of real-world performance. Although outboard insulation and coverings are less likely to diminish the fire rating when tested from the interior side, this may not be the case when assessing an exterior wall assembly from the exterior side, especially with combustible insulation and coverings installed. Consequently, when combustible outboard materials are installed, it is crucial that exterior walls undergo fire resistance testing from both the interior and exterior sides.

Despite the existence of various assessment approaches, new tests may be needed to effectively measure the ability of exterior wall assemblies to resist fire propagation and limit the entry of flames into open eave and attic spaces. Additionally, concerns persist regarding the safety of combustible materials due to flame spread on their exterior surfaces. For instance, the report “California Wildfire Public Policy: Mapping the Wildfire Hazard” by the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS)29 suggests the current requirements of Chapter 7A are insufficient to ensure a house will resist a wildfire. Therefore, it is recommended that Chapter 7A, and other WUI codes, be improved to better address the growing wildfire risks and enhance the resilience of buildings in wildfire-prone areas.

Reducing the roof vulnerability

Roofs are highly vulnerable to ignition because of their relatively large horizontal surface area. Additionally, they require regular maintenance and eventual replacement of their coverings due to exposure to various climatic conditions, including wind, rain, and sun. Consequently, WUI codes such as the 2024 IWUIC and Chapter 7A, typically require Class A roof coverings for their high level of fire performance.30 These coverings help prevent fire spread and penetration through the roof deck from burning embers during wildfires. They are also durable against environmental factors such as high winds and UV exposure, ensuring long-term protection. Numerous Class A roof covering options are available, including asphalt-fiberglass composite shingles, which are effective against severe fire test exposure when installed over underlayments.

Where the roofing profile has an airspace under the roof covering, these same codes also require a cap sheet, the topmost layer in a multi-layer roofing system, that complies with ASTM D390931 and is designed to provide the final layer of protection against the elements, installed over the combustible roof deck. NFPA 1144,32 a standard that provides a methodology for assessing wildland fire ignition hazards around existing structures and provides requirements for new construction to reduce the potential of structure ignition from wildland fires, includes a similar requirement.

Another significant element contributing to the roof’s vulnerability is the roof edge. Gutters and roof-to-wall intersections, where roof covering meets other materials (e.g. siding used in dormers and split-level homes), can be exposed to ember ignition. These areas must be adequately protected. Vents in the under-eave area, being inlet vents, allow air to enter the attic space. During a wildfire, vent openings can then permit wind-blown embers to enter the interior attic space. If combustible materials in the attic ignite, the house can burn from the inside out. The critical need to prevent ember and flame entry through vents during a wildfire, as outlined in Chapter 7A for instance, has led to the development of vents designed to resist the intrusion of flames and embers. Using noncombustible attic insulation can further minimize the risk of attic fires from wind-blown embers.

Although this paper primarily focuses on residential buildings, it is important to note that non-residential structures, such as commercial and institutional buildings, are also located within WUI areas. The inclusion of combustible insulation within Class A roof assemblies is permitted in commercial and industrial buildings constructed in accordance with the International Building Code (IBC). Addressing fire safety in these types of constructions is also important, as they are equally susceptible to wildfire risks and may be co-located with residential structures.

To further enhance the performance of these roofs, builders can install mineral fiber board cap sheets based on ASTM C726, a standard specification which covers the composition and physical properties of mineral fiber insulation board for roof decks as a base for built-up roofing and single-ply membrane systems in building construction.33 It also covers mineral wool roof insulation used as a base for systems such as single-ply, polymer-modified bitumen, and built-up roofing.

Notes

Authors’ note: This article is part one of a two-part series on wildfire resilience in the built environment. Part two will examine practical, community‑scale measures to enhance the safety and resilience of homes and neighborhoods, including the implementation of fire‑safe setbacks and parcel‑level risk assessments, strategies for upgrading existing dwellings, and financing and insurance mechanisms to support and scale home‑hardening efforts. Part one addressed a range of building‑level measures—most notably roof hardening, ember protection, and the use of noncombustible exterior materials—and part two will build on those foundations by focusing on parcel‑ and community‑level implementation and the policy and market instruments necessary to enable broader adoption.

Authors

Tony Crimi, P.Eng., MASc., is the founder of A.C. Consulting Solutions Inc. (ACCS), a firm specializing in building and fire-related codes, standards, research, and product development in the U.S., Canada, and Europe. Before establishing ACCS in 2001, he spent more than 15 years at Underwriters Laboratories of Canada (ULC), where he served as vice president and chief engineer, focusing on codes and standards development, testing, and conformity assessment. With more than 30 years of experience, Crimi has been actively involved in the development of national and international codes and standards through organizations such as the International Code Council (ICC), the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), ASTM, and other leading standards bodies. He has also authored numerous articles and papers on fire protection and facade fire safety.

Antoine Habellion, P.Eng., is the technical director at ROCKWOOL North America, leading the building science, technical services, codes and standards, and product development teams. He oversees a multidisciplinary group that translates research into practical solutions, enhancing the thermal, hygrothermal, fire, and acoustic performance of building envelopes. With over a decade of experience in residential and commercial enclosure design, he contributes to code and standards development, working with industry professionals to advance resilient and sustainable construction practices. Before joining ROCKWOOL North America, he was a building science engineer at ROCKWOOL France in Paris. Habellion holds a Master of Civil Engineering from Hautes Études d’Ingénieur (HEI), Lille, and an Advanced Master’s in Building Science from Arts et Métiers ParisTech and École Spéciale des Travaux Publics (ESTP) in Paris.

Key Takeaways

Wildfire risk in Wildland‑Urban Interface (WUI) areas has escalated dramatically, driven by expanding development and more extreme fire weather, and mitigation requires both building‑level hardening and parcel‑ and community‑scale measures. Exposure to ember and firebrands, radiant heat, and direct flame impingement are the primary ignition pathways; therefore, roofs and exterior walls are critical vulnerabilities that benefit most from targeted interventions. Specifying non‑combustible, ignition‑resistant materials (e.g. continuous mineral‑wool exterior insulation and non‑combustible claddings), improving roof assemblies (Class‑A coverings, cap sheets, edge protection), and incorporating ember‑resistant details (vents, enclosed eaves, sealed penetrations) materially reduce ignition probability and damage severity. Parcel-level strategies—adequate setbacks, defensible space, and parcel-specific risk assessments—complement these measures where spatial constraints limit the separation. Retrofitting existing homes and leveraging financing mechanisms (e.g. PACE), insurance discounts, and incentive programs are essential to scale adoption and make hardening broadly affordable. Empirical analyses indicate that properly implemented mitigation can reduce losses substantially and lower insurance costs. Finally, robust codes, test standards, and coordinated policy and market mechanisms are necessary to institutionalize resilience. Design professionals, regulators, insurers, and homeowners must work together to adopt evidence-based materials, validated assembly testing, and implementation pathways that collectively enhance community resilience to wildfires.