How to weld to vintage structural steels

Structural steel has been used in buildings since the early 1900s. Many of these buildings are still in existence, particularly in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, and are now being repurposed, requiring rehabilitation and/or extension of the original structure. Often, these modifications require welding to the original structural members, which can present challenges regarding the weldability of these vintage steels. This article discusses the issues with welding to vintage structures, the steps involved in conducting a weldability assessment, and some recent project examples.

Steel weldability

ASTM International defines the weldability of a material as “the capacity of a material to be welded under the imposed fabrication conditions into a specific, suitably designed structure, and to perform satisfactorily in the intended service.” Issues with poor weldability of steel can involve limited weld penetration, weld or base metal cracking, and poor mechanical properties of a joint. Cracking can occur through hot tearing during weld solidification, cold cracking of the heat-affected zone (HAZ) after cooling, or lamellar tearing of the joint. Note that structural welding codes, such as American Welding Society (AWS) D1.1, Structural Welding Code for Steel, do not permit the presence of cracks of any size in a welded structure.

Weldability is affected by the alloy composition of the base and filler metals, the thickness of the structural members being joined, and the joint restraint (resistance to thermal shrinkage forces). The skill of the welder is not considered in the weldability of a material, as the welder’s qualifications are designed to ensure that they have the skill to adequately weld a particular joint. Laboratory and field testing have been developed for different materials and joint geometries to ensure that these combinations can be welded without cracking or a deterioration in joint strength or ductility. Historical testing and welding experience have led to the development of welding codes to ensure adequate weldability of joints, such as AWS D1.1, which establishes qualification of the welded assembly and the welder using welding procedure specifications (WPS) and procedure qualification records (PQR).

History of structural steel

Until the mid-1800s, cast iron, which has a carbon content of approximately two to four percent, was the structural ferrous metal of choice, but its applications were restricted by the material’s low ductility and poor structural integrity in tension. Techniques had previously been developed for producing “crucible steel” with a lower carbon content in limited quantities. However, it was not until 1856 when Henry Bessemer developed the “Bessemer Converter” that steel could be manufactured in suitable quantities for mass construction (Figure 1). This steelmaking technique blew oxygen through liquid pig iron, resulting in an exothermic reaction that oxidized impurities in the metal and lowered the carbon content to a level of one-quarter to one percent typical of modern steels. Further modifications to steelmaking, such as the Siemens-Martin Open Hearth Furnace, refined the steelmaking process to improve composition control and lower impurities of the product.

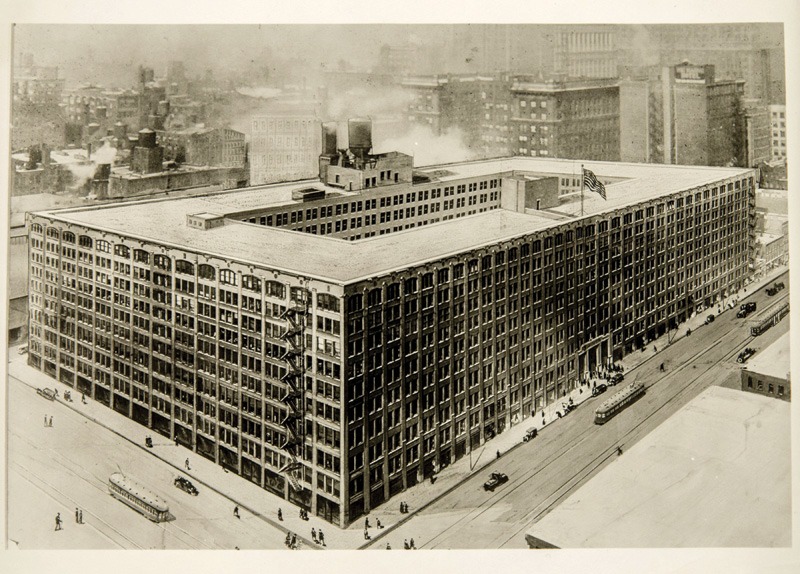

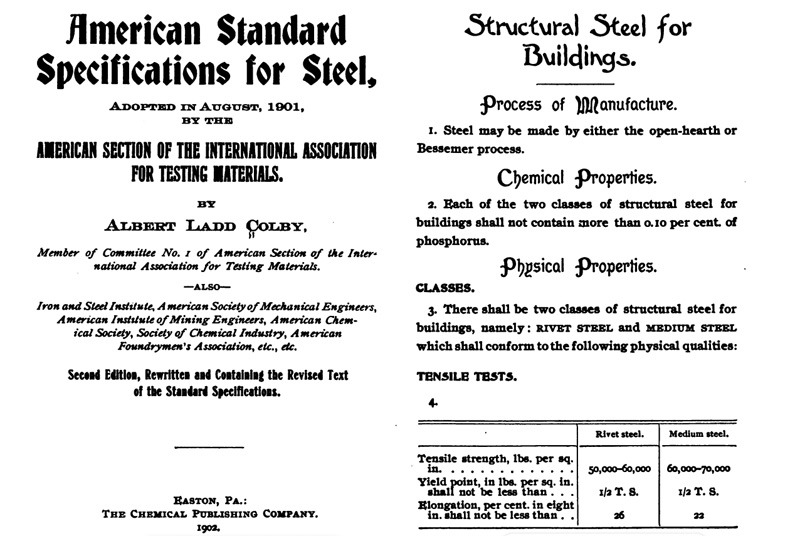

The expansion of the steelmaking industry led to the incorporation of steel into building structures, and in 1889, construction was completed of the Rand McNally Building in Chicago—the world’s first all-steel-framed skyscraper (Figure 2). These early steel structural members were primarily reliant on the iron ore composition for alloy chemistry and were often brittle due to high impurity elements such as sulfur and phosphorus. Issues with quality control and failures led to the formation of the ASTM in 1902. ASTM developed guidelines for the fabrication procedure and test methods to ensure that steels had adequate structural integrity and developed two standards for this purpose: ASTM A7, Structural Steel for Bridges and Ships, and ASTM A9, Structural Steel for Buildings (Figure 3). These steel standards were combined in 1939 and further refined to develop the ASTM A36, Standard Specification for Carbon Structural Steel, which is used today.

Development of arc welding of structural steels

Forge welding, which involves the heating of two pieces of metal and combining them under pressure, has been used for joining metals since ancient times, but is not suitable for mass production. The structural steel elements of the Rand McNally building, which predated arc welding, were joined using rivets. Subsequently, techniques for arc welding were developed, and in 1919, the AWS was formed to advance welding science and technology. However, the shipbuilding industry was the primary adopter of welded joints, and it was not until after World War II that welded joints became commonplace in building structures.

Early steel standards considered only the mechanical properties of the base metal and not the weldability of the material. For example, an early 1909 ASTM A9 standard for structural steel specified tensile testing to ensure a tensile strength of 345 to 414 MPa (50 to 60 ksi) for rivet steel, with a yield strength greater than half that of the tensile strength and a minimum elongation of 26 percent. The only limitations on composition were on the impurity elements, sulfur and phosphorus (0.06 and 0.08 percent respectively), as these were known to embrittle the material. In the words of the standard, “where the physical properties desired are clearly and properly specified, the chemistry of the steel, other than prescribing the limits of the injurious impurities, phosphorus and sulphur, may in the present state of the art of making steel be safely left to the manufacturer.”

This lack of control of alloying elements in early structural steel creates issues when welding to these materials, as the alloy composition is now known to significantly affect the weldability of a steel. Therefore, when welding is required to vintage steel structures, the welding process must be approached with caution.

Welding to vintage steels

Note that this article is focused on the weldability of steels. When field welding to existing structures, other considerations, such as the effect of welding heat and stress on the original structure, must be considered. Numerous references, such as Ricker’s American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC) publication, discuss these considerations and provide common techniques for structural support and reinforcement.

Welding standards such as AWS D1.1 ensure the weldability of steels using qualification testing of test welds. This involves mechanical testing of the joint using tensile or bend tests, and microstructural assessment (the macroetch test). Testing is required whenever the material, geometry, or welding process is changed. To alleviate the need for this qualification testing, commonly used structural steels, such as ASTM A36 and A572, are prequalified by AWS D1.1 for different geometries and section thicknesses. The chemical composition control of the base metal, the weld process variables, and the qualification of the welder ensure the joint can be readily fabricated without defects.

However, prequalified welding is designed for new construction using known materials. When welding to existing structures containing vintage steels, the original material is unknown. If sections of the original vintage steel can be removed, then qualification testing is possible. There is a chapter within AWS D1.1 (Clause 11 Strengthening and repairing of Existing Structures) that deals with this process. However, in many situations, there is no spare original material that can be removed for testing, so the weldability of the material must be determined using a more fundamental method.

Testing vintage steel for weldability

The easiest method to determine the weldability of a vintage steel structure is to determine if existing welds have been successfully made to the structure. If welds are present and visual inspection reveals the joints to be sound, then the weldability of the steel is likely adequate. However, in most cases, joints will have been formed using riveting or bolting, so additional investigation is required.

The chemistry of the existing steels can be determined using laboratory analysis techniques according to standards such as ASTM E350. These techniques typically require only a small section of material (less than 1 oz weight) and can be removed from a low-stressed location so as not to significantly impact the original structure. Note that when removing a sample, it is important not to overtly heat the metal, which can oxidize it and change its properties. Therefore, reciprocating or abrasive saws should be used for sample extraction, never flame cutting. In a pinch, cuttings from drill swarf can also be used for composition testing, but solid material is always preferable for uniformity.

It is important to note that field measurement of carbon steel composition cannot reliably be conducted using hand-held XRF detectors. The instruments are primarily designed for the identification of non-ferrous metals and have poor resolution of the carbon and impurity content necessary to determine weldability.

When measuring the composition of vintage steel members, it cannot be assumed that all components were fabricated from the same heat lot; therefore, testing of multiple members is desirable.

The results of the steel composition analysis can be used to determine the material’s susceptibility to cracking. Hot cracking or tearing of weld metal occurs when impurity elements, such as sulfur and phosphorus, segregate during solidification, creating areas of low-melting-point metal that are vulnerable to cracking during thermal shrinkage. ASTM A36 requirements limit the sulfur and phosphorus composition to 0.05 and 0.04 percent respectively. If the steel composition analysis shows these impurity elements do not significantly exceed these limits, then hot cracking is unlikely to occur.

Cold cracking in steels occurs when a brittle microstructure is formed during cooling. The susceptibility of the formation of this brittle microstructure increases with the alloy content; hence, preheating is used during the welding of higher alloy steels to slow the cooling rate and reduce the probability of the formation of this deleterious microstructure. The susceptibility of an alloy to cold cracking can be quantified by the carbon equivalent (CE) and the standard AWS calculation for this is:

The composition analysis of the vintage steel can therefore be used to calculate its CE. As a general rule, if the CE is less than 0.4 percent, then the likelihood of cold cracking after welding is minimal. However, at high levels of CE, preheating of the joint will be required.

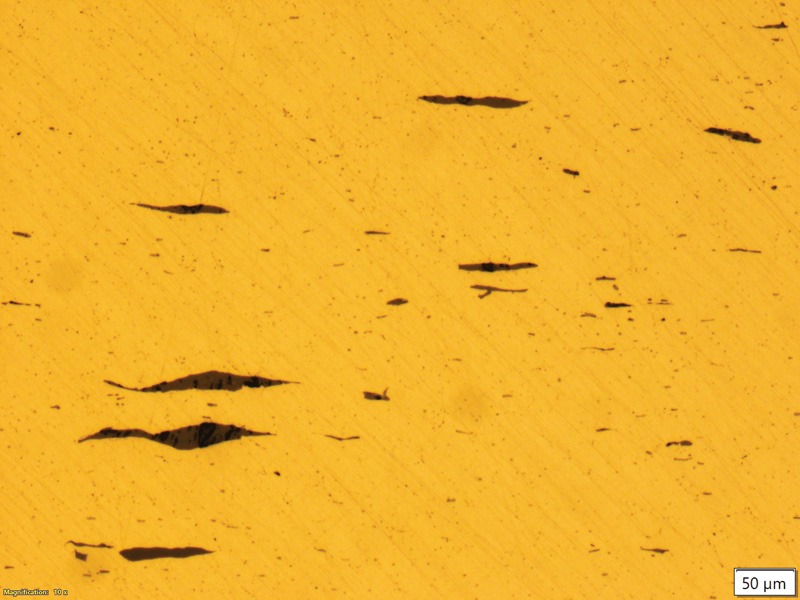

Finally, lamellar tearing can be an issue for vintage steels, which is a mechanism where cracking/tearing of the material occurs when a rolled plate or shape is subjected to through-thicknesses stress. This is caused by intermetallic (primarily manganese sulfide) inclusions that form in the rolling plane during processing, creating weaknesses along the through-thickness axis. These inclusions, known as stringers, are common in vintage steels. There is a metallurgical test, ASTM A770, that can be conducted on a small 13 x 13 mm (0.5 x 0.5 in.) section of original material to determine the susceptibility to lamellar tearing. If the material is found to be susceptible to lamellar tearing, then the AISC Steel Construction Manual and AISC Design Guide 21 have guidelines for the modification of joint design to mitigate the risk of lamellar tearing.

Welding procedure modification and inspection techniques

Composition analysis of vintage steel ofteOOS reveals that it meets the requirements of ASTM A36 steel, and thus, it can be considered a prequalified material and readily welded. However, for materials where composition testing has suggested that the weldability of the original steel is less than ideal, weld procedure modification and inspection techniques can be employed to ensure that a sound weld is produced.

If the composition analysis shows that high levels of sulfur and/or phosphorus are present, then the occurrence of hot cracking can be minimized by lowering the heat input of the weld. Using stringer beads along the weld and extending interpass time is a common technique. After welding, 100 percent inspection of the weld metal is preferred to search for hot tears. As these cracks can form under the surface of the weld metal, non-destructive examination (NDE) techniques such as magnetic particle (MT) inspection or ultrasonic (UT) are preferred, if the weld geometry allows this technique to be employed.

If the CE of the material is greater than 0.4 percent, then preheat of the joint must be conducted prior to welding. AWS D1.1 contains guidelines for determining the appropriate preheat according to steel composition, joint thickness, and weld restraint. In addition, appropriately-stored low-hydrogen electrodes must be used to minimize the probability of cracking. Hundred percent visual inspection and/or dye penetrant (PT) testing of the HAZ is required. Per AWS guidelines, inspection for cold cracking should be delayed at least 48 hours after welding, as these cracks can form over time.

Unfortunately, the composition of some vintage steels can be so extreme that welding is not possible. If weld process modifications are unable to prevent joint cracking, then an alternate joining method (bolting) must be employed.

Project examples

Table 1

| Composition analysis of vintage steels compared to ASTM A36 requirements |

||||||

| Element percent | 1898 | 1900 | 1902 | 1905 | 1909 | ASTM A36 |

| Carbon | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.21 | <0.25 |

| Manganese | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.8-1.2 |

| Silicon | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | <0.4 |

| Sulfur | 0.35 | 0.027 | 0.023 | 0.27 | 0.041 | <0.05 |

| Phosphorus | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.036 | 0.09 | 0.031 | <0.04 |

| Carbon Equivalent (CE) | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.34 | –

|

Compositions with red font do not meet the ASTM A36 requirements.

Recently, there was a weldability analysis of a number of steel-framed buildings in New York and Chicago constructed before 1909, when the ASTM A9 specification was developed. The composition analysis of these steels is listed in Table 1 and compared to the modern requirements of ASTM A36 steel.

It can be seen that the composition of these vintage steels is generally not extreme and is indeed similar to that of modern steels. The CE of these steels is all less than 0.35 percent. The manganese levels of these steels tend to be lower than modern materials, but this impacts the hot workability of the material rather than the weldability. Apart from the 1898 and 1905 dated steels, the sulfur and phosphorus levels were close to modern requirements and should be considered weldable with the weld modification and inspection techniques mentioned above.

Conclusion

In conclusion, structures containing vintage structures can be implemented with a cautious approach. This article introduces the concept of weldability in steel. Material composition analysis must be conducted to determine the weldability of the steel, and depending on the findings, subsequent modifications in the welding procedure and post-weld inspections are implemented to achieve satisfactory results.

References

- AISC Steel Construction Manual 2023 PART 8— Design Considerations for Welds; Other Specification Requirements and Design Considerations; Lamellar Tearing.

- AISC Design Guide 16 2024: Assessment and Repair of Structural Steel in Existing Buildings.

- AISC Design Guide 21 2017: Welded Connections—A Primer for Engineers.

- ASTM E350 2018, Standard Test Methods for Chemical Analysis of Carbon Steel, Low-Alloy Steel, Silicon Electrical Steel, Ingot Iron,

and Wrought Iron. - ASTM A770 2018, Standard Specification for Through-Thickness Tension Testing of Steel Plates for Special Applications.

- AWS D1.1 2025: Structural Welding Code – Steel.

- ASM Handbook Volume 6 1993: Welding, Brazing, and Soldering.

- Ricker, David AISC Engineering Journal, Vol. 25, pp. 1-16 1988: Field Welding to Existing Structures.

- Raymond, Robert, Pennsylvania State University Press 1985: Out of the Fiery Furnace, The Impact of Metals on the History of Mankind.

Authors

Alan O. Humphreys, Ph.D., P.E., is a senior technical manager and metallurgical engineer in Simpson Gumpertz & Heger’s (SGH) engineering mechanics and infrastructure division. He specializes in the failure analysis and structural assessment of materials systems that have degraded by mechanisms such as corrosion, fracture/fatigue, or wear. Humphreys has an extensive technical background in laboratory testing and analysis to ASTM/NACE/API standards. He can be reached via email at aohumphreys@sgh.com.

Dustin A. Turnquist, P.E., CFEI, is a project director with Simpson Gumpertz & Heger’s (SGH) engineering mechanics and infrastructure division. He is a recognized leader in metallurgy and materials science, specializing in failure analysis, product performance, and materials selection across various industries. With deep expertise in corrosion, fatigue and fracture characterization, and root-cause analysis of complex material failures, Turnquist leads large-scale investigations into significant failures and losses, spanning aerospace, automotive, power generation, healthcare, and heavy industry. He can be reached at daturnquist@sgh.com.

Key Takeaways

Structural steel used in early 20th-century buildings is often still in service today, requiring careful evaluation when welding to original members. This article explains how weldability is influenced by alloy composition, impurities, and carbon equivalence, and outlines methods for assessing vintage steels through material testing and modified welding procedures. It also highlights inspection practices and real-world project examples demonstrating how thoughtful analysis enables safe, reliable rehabilitation of historic steel structures for modern use.