Refined concrete: A measurable path to performance and sustainability

In the ongoing discourse on hard-surface flooring, the distinction between polished and refined concrete has moved beyond terminology and into a critical discussion about performance, durability, and accountability. Recent exchanges1 in 2025 between the Concrete Polishing Council (CPC) and the authors of the article “Refine Versus Shine: Defining and Defending Design Intent with Refined Concrete”2 have underscored fundamental philosophical differences in how the industry defines, measures, and delivers exposed concrete surfaces. However, the two are not the same. Polished concrete offers a variety of topical final products that lead to a gloss benchmark finish, whereas refined concrete, as defined by the National Concrete Refinement Institute (NCRI), involves the physical modification of the concrete itself to produce a floor finish.

These conversations have also clarified important distinctions not only between the two work results but also within each category, offering a clearer understanding of both polished and refined finishes.

A fundamental shift in understanding

Over the past decade or more, the term “polished concrete” has served as the industry’s catch-all phrase for a floor that looks like an exposed concrete finish. Over time, however, the label has become diluted and now encompasses a wide range of systems—including resin-bonded abrasives, film-forming sealers, grind-and-seal processes, densified surfaces, and high-build coatings—many of which merely imitate the original definition of polished concrete appearance through clear topcoats.

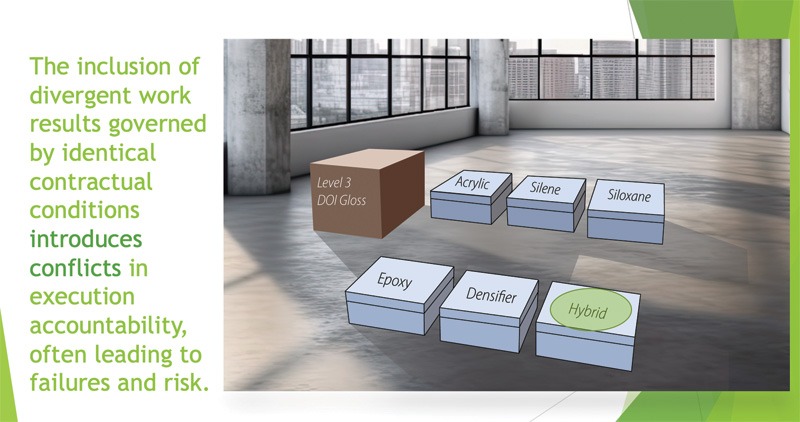

These softer, often short-lived materials typically do not offer the same long-term durability and performance as genuine surface refinement of the concrete itself. If these alternative systems were pigmented like traditional coatings, it would be far easier to distinguish actual concrete from a coated surface, but because these different work results look similar and are graded by identical contractual conditions (e.g. DOI-gloss), conflict is introduced to accountability, execution, maintenance, and risk.

“Refined concrete” restores the material’s inherent integrity. It prioritizes measurable surface refinement over temporary gloss or resin sheen, redirecting focus to quantifiable outcomes: surface hardness, coefficient of friction (COF), surface texture, and lifecycle durability. In this way, it elevates a concrete finish to a robust building system.

Why polished concrete became problematic

Organizations such as the CPC and the American Society of Concrete Contractors (ASCC) appropriately reference standards such as ACI-ASCC 310.1 to guide DOI gloss levels for polished concrete. However, as the authors of “Refine Versus Shine” point out, these specifications—while valuable—are often applied inconsistently and rely on subjective language. This does not mean that high-quality polished concrete floors are not being installed in some instances; rather, it underscores that, unlike most definitions of polished concrete, which are governed by similar contractual conditions, these inconsistencies introduce conflicts in execution and accountability.

Design teams and contractors interpret “polished” in widely varying ways. Many systems depend on (or even mandate) resin topcoats, epoxy grit tooling, or non-cementitious (i.e. polyurethane, acrylic, etc.) grout coatings that can conceal refinement deficiencies rather than actually resolving them. Others employ multiple layers of lower Mohs-hardness stain sealers—informally dubbed “pay-juice” by some contractors—as shortcuts to aesthetic distinctness-of-image (DOI) gloss targets that ensure contract disbursement, but leave owners with surfaces prone to premature failure, inadequate maintenance tolerances, and frequent refinishing during operational lifecycles. This does not mean that all polished concrete installers operate in this manner, but language vagueness can breed contractual risk: misaligned appearance or performance can trigger disputes, delays, and unforeseen costs. Refined concrete counters this with objective metrics and precise terminology to safeguard all stakeholders.

Polished and refined: What is the difference?

Polished concrete and refined concrete are fundamentally different processes that produce different results. Originally, the idea of polished concrete relied on creating a precise, methodical scratch pattern, removing more of the concrete surface through multiple passes of diamond tooling with finer and finer grit steps, similar to sanding wood. In theory, the gloss should originate from the scratch sequence itself; however, in reality, achieving this level of precision consistently across a concrete slab is extremely challenging. As a result, the measurable shine (the condition of the contract) is partially or totally derived from the application of acrylics and other sealer types, as well as resin transfer from certain epoxy tool types, rather than the tighter and tighter scratch pattern.

Refined concrete does not depend on scratch pattern choreography to produce gloss or other performance characteristics. While grit progression and proper tooling still matter, the work product is driven by chemistry and craftsmanship, measured at every step. Re-emulsifying and rolling the surface, locking fines back into the slab to correct the surface texture, rather than grinding down the surface and filling with repair materials, yields a refined finish. Surface clarity, hardness, and durability originate from the concrete itself, rather than from applied films, resinous fillers, and “pay-juice.” In polishing, surface performance reflects not only how well the scratch sequence was executed but also how acrylic and other surface films are maintained. However, with refinement, surface performance becomes inherent to the slab, achieved through mechanical control and slurry chemistry, and is not dependent on coatings.

Quantifiable refinement over gloss

Refined concrete’s hallmark is its emphasis on verifiable surface refinement, assessed through standardized metrics such as:

- Distinctness of Image (DOI) and roughness average (Ra)—Ensuring optical clarity stems from physical refinement, not coatings

- Coefficient of friction (COF)—Confirming safe traction across hard surfaces according to ANSI/NFSI B101.3

- Mohs scale of surface hardness—Targeting values above seven for superior durability, reduced wear, and extended maintenance intervals

- Roughness average (Ra)—20 μin or below as a minimum contractual threshold

Deb Suchomel, a senior project manager at QTS Data Centers, states that “using simple field benchmarks like Ra (surface roughness), DOI gloss, and Mohs helps keep the whole project team aligned.”

The Mohs scale: Comparing floor finishes

The Mohs Scale, developed by Friedrich Mohs in 1812, ranks materials from one (talc) to 10 (diamond) based on scratch resistance. Building products often exhibit hardness ranges due to composite compositions.

Refined concrete achieves higher Mohs hardness values than many coated or polished systems, resulting in reduced maintenance in high-traffic environments and eliminating the need for coatings or waxes. Coated or waxed floors, which typically have lower surface hardness, require more frequent upkeep under heavy use because they are less resistant to wear and tear.

Understanding the minimum acceptable thresholds for scratch resistance helps determine the appropriate flooring system. For example, areas with lighter foot traffic—such as office spaces—may only require a Mohs hardness of four or greater, as suggested by the CPC for polished concrete. In contrast, schools, industrial facilities, and environments with heavy foot traffic or hard-wheeled equipment may be better served by refined concrete, which routinely reaches Mohs hardness values of seven, eight, or even nine.

Project collaboration

Successful outcomes hinge on the general contractor (GC) and site supervisor fostering open dialogue among architects, designers, subcontractors, and suppliers. Clearly defined roles and shared lessons from prior projects enable proactive adjustments.

- Pre-installation meetings—Involve architects, interior designers, and structural engineers to align structural and aesthetic goals, coordinating with contractors to achieve success

- Supplier and finisher involvement—Early discussions and initial surface measurements ensure workability without compromising refinement potential. Site conditions inform curing regimes to optimize slab acceptance and setting the canvas for the refinement crews

Mockups: Where quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) meet

Risk management in any concrete finishes blends artistry and rigor, with mock-ups serving as the critical bridge to full-scale production success, the initial manifestation of design intent and owner needs. Refined concrete finishes, as with polished finishes, benefit from structured mock-up protocols and on-site validation to align expectations, mitigate risks, and deliver consistent results. Just as reliable standards emerge from coordinated batching and placement, the same responsible party overseeing mock-ups should also manage the full-scale refinement process.

- Personnel continuity: Assign the same skilled personnel from mock-up creation through installation to ensure expertise and accountability.

- Tangible benchmarks: Mock-ups provide physical proof that owner requirements are achievable, setting a clear standard for the outcome.

- Progressive staging for iterative review:

- Require at least two mock-ups: the first a 3.05 x 3.05 m (10 x 10 ft) panel, the second a 7.62 x 7.62 m (25 x 25 ft) area, positioned in varied locations to assess the impact of lighting, environmental conditions, concrete quality, and finishing techniques. An acceptable Ra benchmark for finished concrete before polishing, refining, or sealing is 100 micro inches or less (as measured by ASME B46.1-2009, Surface Roughness, Waviness, and Lay).

- The initial mock-up validates surface micro-texture, color, aggregate exposure, DOI-gloss, Mohs scratch hardness, and dynamic coefficient of friction (DCOF) for refinement.

- The second incorporates project-specific elements—control joints, area drains, changes in plane, and simulated repairs—to mirror real-world challenges.

- Larger projects may warrant additional mock-ups to evaluate performance across diverse site zones. Smaller projects may only provide for one mockup.

Post-approval, a robust QA/QC program—ideally supported by a special inspector experienced in refined concrete—enforces standards through systematic inspections, surface texture evaluations, and color-consistency checks.

The NCRI also provides on-site QC and documentation, and can revoke credentials for installers who do not meet the contractual requirements outlined in their boilerplate specification. Detailed documentation, including photographs and written observations, creates an audit trail that allows for rapid identification and resolution of issues.

Environmental factors, including temperature, humidity, and direct sunlight, significantly impact the quality of concrete. Controlled temporary lighting, heating, and ventilation are essential to optimize these conditions. By contractually requiring protection of the mockup as part of the final QC conditions, a team can anticipate and verify site-specific variables, ensuring outcomes align with the designer’s original intent, and avoid, therefore, theoretical requests for information (RFIs) on what the mockup might have measured out at.

Thorough planning and communication—from mock-up to completion—yield refined finishes that can be verified from paper to concrete surface. This systematic approach not only enhances communication and reduces risk but also contributes to overall project success, producing surfaces that are far more durable and lower-maintenance than coating-dependent systems (e.g. epoxy, acrylic, urethane, or polyaspartic), which require frequent reapplication in contrast to refined concrete’s inherent longevity.

Maintenance that mirrors installation

A certified refinement installer (CRI) from NCRI should understand the refined concrete approach well enough to distinguish between the various types of polished work results and refined concrete. This is critical when working with owners who have only experienced design, installation, and maintenance of various polished/hybrid concrete floor finishes. It is possible to have an owner with polished concrete floors installed in multiple buildings, each at various stages in its lifecycle, and maintenance staff executing maintenance procedures tied to maintenance materials, supplies, and equipment, all based on various polished concrete floor finishes. To this owner, a shift in approach must consider the impact on maintenance practices and supplies/equipment. The necessity of this shift is questioned when the polished concrete floor finish is not a point of critique. This is where mockups and on-site training resources are useful.

Owners who manage multiple buildings can benefit from gradually incorporating refined concrete finishing techniques. They should start with the current project in design or the floor they are interested in, and then improve previously installed polished concrete floors. This process will change them from polished to refined concrete floors, extending their lifespan and making maintenance easier. The maintenance benchmarks are identical to installation benchmarks. Ra, Mohs, DOI-gloss, and DCOF equip facility maintenance teams to monitor performance contractually. DOI-gloss and Ra correlate with COF; low DOI may also signal contamination, reducing traction. As specification consultant Larry Hale notes, “A major advantage of refined concrete is a DCOF independent of applied coatings.” Tracking integral benchmarks without re-coating aids in reducing lifecycle costs, while also helping to maintain safety, health, and other performance requirements.

Reducing contractual risk

Without quantifiable specifications to define contractual requirements, project teams will continue to receive concrete floors prone to change orders, performance inconsistencies, and high maintenance costs. Designers and contractors will continue to exhaust contingencies without understanding what went wrong or how to avoid similar issues in the future.

Specifications serve not just as technical guidance but as risk instruments—and vague language invites conflict. Refined concrete offers to address this by establishing clear pre-grind criteria, including mock-ups with defined metrics for color and gloss, scratch resistance, and more. Along with verified materials and documentation. These objective benchmarks protect all parties from ambiguity and post-occupancy failures. The industry is now advancing toward accountable language and precise definitions that can be universally specified to solve concrete floor challenges reliably. The focus has shifted from describing processes to demanding results—quantifiable, repeatable, and validated through physical testing of the finished product delivered to the client, fostering alignment and confidence across the design and construction team.

Final finish

Polished concrete and refined concrete are different floor types, and the polished-versus-refined debate is structural, not semantic; as it opens up the question of whether to rely on appearance standards or adopt performance-driven systems that safeguard owners, empower specifiers, and advance sustainability. Chris Bishop, NCRI president, remarks, “I’ve watched owners embrace 03 35 493 refined finishes for a superior look and simple, verifiable metrics that prove they’re getting what they paid for, while contractors value the training and clearer design-team alignment. Owners eliminate chronic floor issues, and schedules shrink because precise measurement speeds installation.”

Luis Adan, director of Capital Projects at North Kitsap School District, says, “As a public owner responsible for long-term facility performance, we’ve found refined concrete to offer a superior balance between safety, aesthetics, and lifecycle value. In high-traffic school environments, refined concrete maintains a higher coefficient of friction when wet compared to traditional polished floors, reducing slip hazards for students and staff. It also requires less intensive maintenance, with fewer burnishing cycles, lower chemical usage, and reduced equipment wear, while retaining a clean, uniform appearance. The result is a safer, more cost-efficient floor solution that aligns with both our durability standards and operational budgets.”

The industry is learning that slowing down to read the floor is ultimately the fastest way to finish strong. And, as Deb Suchomel explains, “When everyone understands what’s being measured—and why—it becomes far easier to deliver consistent, high-performance finishes that everyone is proud of.”

Notes

1 Read the Concrete Polishing Council (CPC) letter to the editor in response to the authors’ “Refine Versus Shine” article, as well as the authors’ response on pages 7-10 published in The Construction Specifier’s April 2025 issue.

2 Refer to the article Refine Versus Shine: Defining and Defending Design Intent with Refined Concrete, written by Kristina Abrams, AIA, LEED AP, CDT, CCS, Chris Bennett, CSC, iSCS, CDT, Bill DuBois, CSI, CCS, AIA,

Melody Fontenot, AIA, CSI, CCCA, CCS, Kathryn Marek, AIA, CSI, CCCA, NCARB, SCIP, Keith Robinson, RSW, FCSC, FCSI, LEED AP, Ryan Stoltz, P.E., LEED AP, Vivian Volz, CSI, AIA, LEED AP, SCIP, published in The Construction Specifier’s January 2025 issue. Read the article here.

3 Refer to 03 35 49 Refined Concrete Finishing guide specification and other information, including certified refinement installers (CRIs) at the National Refined Concrete Institute’s (NCRI) training and resources page.

Many low-Mohs-hardness sealers and coatings—nicknamed “pay-juice” by contractors—are marketed as quick fixes for achieving high gloss/DOI, but do not necessarily address the concrete itself, leaving surfaces prone to premature failure throughout their service life despite meeting the gloss benchmarks. Refined concrete uses its own matrix to create a floor finish versus other types of traditional floors that get filled up and coated with polyurethane, epoxies, acrylics, and other non-cementitious materials.

Photo courtesy National Concrete Refinement Institute (NCRI)

The Mohs numbers matter

The Mohs Scale of Hardness is a qualitative ordinal scale designed to assess the scratch resistance of minerals and related materials. Established by German geologist Friedrich Mohs in 1812, this scale ranks substances from 1 (softest) to 10 (hardest), according to their capability to scratch one another. When assessing building materials, it is important to recognize that products often contain a mix of substances, resulting in a range of hardness values rather than a single fixed number.

The chart illustrates the relationship between material hardness, use, durability, and upkeep. Refined concrete has a higher Mohs hardness than coated polished concrete, meaning less maintenance in busy areas and no need for coatings or waxes. In contrast, surfaces protected mainly by coatings or waxes tend to have lower hardness and require more frequent maintenance in high-traffic settings.

| Material | Mohs Hardness | Composition | Application Notes | Other Hardness Scale |

| Soft Materials (Mohs 1 to 3): Low Foot Traffic Floor Finish

Soft materials, such as limestone and wood, are commonly used in decorative, low-foot-traffic flooring applications due to their ease of shaping and aesthetic appearance. These materials are less resistant to scratching from common objects. |

||||

| Limestone | 2 to 3 | Calcite | ||

| Travertine | 3 to 4 | Type of limestone | ||

| Marble | 3 | Metamorphic limestone | ||

| Resinous Coatings | 2 to 3 | Polymeric material/soft, viscoelastic | Mohs is typically not used | Shore D Hardness 70 to 90 |

| White Oak | 3 | Wood species | Mohs is typically not used | Janka Scale 1,360 lbf (6,050 N) |

| Medium Hard Materials (Mohs 4 to 6): Medium Foot Traffic Floor Finish

Medium-hard materials such as slate, ceramics, tropical hardwoods, and glass are valued for their balance of durability and workability, making them suitable |

||||

| Ipê | 5 | Wood species | Mohs typically not used | Janka Scale 3,684 lbf (16,390 N) |

| Slate | 5 to 6 | Often contains quartz | ||

| Glass | 5.5 to 6 | Low-iron glass may be softer | ||

| Ceramic Tile | 5 to 7 | Clay type and firing process | ||

| Plain Concrete | 5.5 | Standard smooth troweled finish | Hardness can be improved by adding granular hardeners or liquid applied surface refinement |

|

| Plain Concrete w/ Hardener/Densifier | 6 | Sodium silicate, lithium silicate | Liquid silicate based surface treatment |

|

| Basalt (traplock) dry-shake | 6.5 | Crushed aggregate | Industrial floor finish | |

| Hard to Very Hard Materials (Mohs 7 to 9): High Foot Traffic Floor Finish

Hard materials such as granite and porcelain are preferred for high-traffic areas due to their superior scratch resistance. Very hard materials, such as |

||||

| Granite | 6 to 7 | Quartz, Feldspar | ||

| Porcelain Tile | 7 to 9 | Extremely dense and hard | ||

| Refined Concrete | 7 to 9 | Quartz or Feldspar crushed gravel | ||

| Silica Dry-shake Finish | 7 | Quartz or Feldspar fine aggregates | ||

| Corundum Dry-shake Finish | 8 | Crystaline aluminum-oxide fine aggregates |

||

| Metallic Dry-shake Finish | 8.5 to 9 | Iron-based fine aggregates | Rusts in areas prone to wetting | |

| Chimeric Materials (Mohs 3 to 7+)

Chimeric materials such as terrazzo display variable hardness across their surfaces due to the composition and proportion of aggregates and binders. |

||||

| Cementitious Terrazzo | 6 to 8 | Portland cement binder | Reduced aggregate bond strength versus epoxy resin Terrazzo | |

| Epoxy Resin Terrazzo | 3 to 6 | Polymeric resin binder | Enhanced aggregate bond strength versus cementitious Terrazzo | |

Authors

Kristina Abrams, AIA, iSCS, LEED AP, CDT, CCS, is an architect with 20-plus years of experience, directs specifications at O’Connell Robertson, emphasizing early clear terminology to align drawings and specifications.

Chris Bennett, CSC, iSCS, CDT, is a Portland-based construction consultant, educates owners and their AEC teams to deliver a stronger, lower-cost, lower-impact concrete systems that save budget, carbon, time, and water.

Bill DuBois, AIA, CSI, CCS, is an architect who champions team collaboration to deliver clear, risk-reducing specifications that maximize value and enable powerful design solutions.

Ken Hercenberg is a senior specifier at Corgan, with more than 40 years of experience, specializing in project manuals, building envelopes, code reviews, and sustainability.

Ashley Houghton, CDT, LEED Green Associate, is a specification writer at Perkins&Will and a board member of the Construction Specifications Institute’s (CSI) Austin chapter. She has worked on refined concrete projects in the South-Central U.S.

Donald Koppy, CSI, CCS, AIA, NCARB, is a master construction specifier/architect with more than

40 years of experience. He is licensed in 10 states, leading nationwide projects with expertise in coordination with BIM.

Kathryn Marek, AIA, CSI, CCCA, NCARB, SCIP, is a specifier and an architect. She is the principal at KM Architectural Consulting and the current president of SCIP.

Mitch Miller, with 45 years of technical experience, leads M2 Architectural Resources in specifications, QA/QC, and building-envelope commissioning, and teaches CSI CDT courses.

Keith Robinson, RSW, FCSC, FCSI, is an Edmonton, Alta-based architectural technologist and specifier. He instructs courses for the University of Alberta, and advises ASTM/NFPA standards committees.

Linda Stansen, CSI, CCCA, RA, SCIP, is a California-licensed architect and specifier with over 30 years of experience. She leads a woman-owned firm that specializes in sustainable, comprehensive specifications for diverse public/private projects.

Michael Thrailkill, AIA, CDT, NCARB, LEED AP, is a licensed architect in Oregon and Florida with over

30 years’ experience. He leads M. Thrailkill.Architect, providing specifications, project manuals, and material research nationally and internationally.

Vivian Volz, AIA, CSI, LEED AP, SCIP, is an independent specifier for commercial, public, and multifamily projects in California and beyond.

Justin R. Wolf is a Maine-based writer covering green building, energy policy, manufacturing, and regenerative design.

Anne Whitacre is a specifications writer with more than 40 years of full-time experience at firms in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. She has been a CSI member for more than 40 years and was elevated to Fellow in 2006.

Key Takeaways

The 2025 dialogue revived a key distinction between polished and refined concrete, shifting attention from appearance to measurable performance. Refined concrete prioritizes durability, clarity, safety, and long-term value using quantifiable metrics like Ra, Mohs hardness, and DOI gloss—reducing maintenance and contractual risk. Unlike polished concrete, which often depends on coatings and vague definitions, refined concrete delivers performance through its inherent properties. With clear specs, mockups, and collaboration, it restores material integrity and provides a verifiable, repeatable, low-maintenance solution for owners and specifiers.