Thermal efficiency in glazed curtain wall systems

Image courtesy Azon

Image courtesy Azon

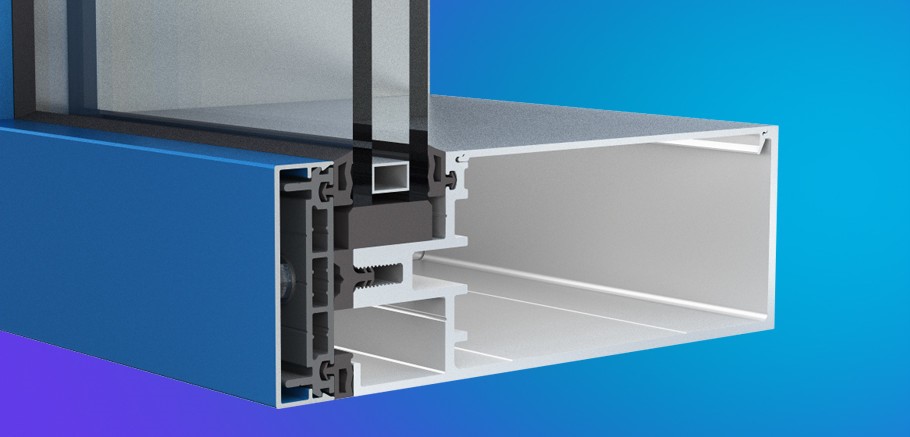

Dual thermal barrier

If one debridged cavity performs well, then two will perform even better in many instances. In dual thermal barrier systems, the U-factor can improve by as much as 20 percent, depending on cavity size and location, and fenestration type. Greater condensation resistance can also be achieved. Additionally, the dual cavity allows for wider span openings for greater glass area and, consequently, increased daylighting. Dual thermal barrier designs also allow for the use of triple-glazing for U-factors of <0.20.

Polyamide thermal barrier strips

Polyamide barriers represent an alternative to the polyurethane-based pour-and-debridge method. They are pre-extruded, structural polyamide insulating strips that usually have multidirectional glass fiber reinforcing to improve load transfer.

For wall systems utilizing polyamide strips, two separate aluminum extrusions are designed—one interior and one exterior—and channels in the aluminum profiles are created to hold the barrier strips. These channels must be knurled to produce teeth that improve the shear strength of the assembly, as well as hold the polyamide strip and prevent shrinkage. (In many curtain wall applications, the shear strength of the composite is typically not critical because the composite I value comes from the interior tube. Shear values for composite assemblies using strips generally achieve between 3560 N and 9785 N for 100-mm (800 and 2200 pounds of force for 4-in.) section. Additionally, there is thermal cycling data in which there is minimal drop in shear after field exposure or thermal cycling.) Once the polyamide strip is inserted into the aluminum’s channel, the entire assembly is rolled, or crimped, to create the mechanical bond and turn the system into a composite.

Image courtesy YKK AP

Advantages of the polyamide thermal barrier strips include:

- greater thermal separation with the use

of less metal; - some of the greatest thermal separation widths available;

- use of less metal, enabling conservation of resources; and

- polyamide can be recycled.

The strips also have a similar coefficient of expansion and contraction to aluminum, ensuring the system’s overall stability.

Since the interior mullions are completely separated from the exterior ones in these unitized systems, a benefit of the method is they can be finished independently from one another. This gives designers the option of specifying high-performance coatings on a building’s exterior while choosing another, more suitable option for the interior, such as a coating that is highly mar-resistant or lower in cost.

Ongoing developments in curtain wall systems include alternative designs for pressure plates. Polyamide was used to develop a new pressure plate system that is up to 20 percent more efficient than earlier designs and has a 10 percent gain in condensation resistance factor. Pressure plates with polyamide have excellent thermal values and require no special handling or fabrication. They are installed similarly to aluminum pressure plates.

Conclusion

The curtain wall and glazing design and manufacturing industry has come a long way in reducing unwanted heat loss/gain from building interiors. The steady evolution of fenestration assemblies has ensured this advancement. An advantage is many of the improvements bring additional benefits, such as controlling condensation and creating more choices for coatings.

Chad Ricker is a market team manager at Technoform North America, where he has worked for more than 20 years. He has an engineering background, graduating from East Tennessee State University with a master of science in technology with a concentration in engineering. He can be contacted via email at chad.ricker@technoform.com.

Ben Mitchell, CSI, is a coatings industry veteran with more than 35 years of experience in architectural aluminum coatings. Retired as of 2026, he most recently served as business development manager for architectural coatings at Axalta. His career also includes roles at Valspar Corp., and AkzoNobel where he started in 1990 as a lab chemist formulating (PVDF) coatings before moving into product management.

Jerry Schwabauer is retired from a long career in the fenestration industry, with many years spent in senior sales and marketing leadership roles at Azon. He was active with the American Architectural Manufacturers Association and was a frequent speaker on optimizing thermal performance in commercial fenestration in North America and Asia.