When Wetter May Be Wiser: Designing for resilience in areas subject to flooding

by Tom Little, CFM, CGP

Recent storms of force and impact far greater than previously imagined possible have been devastating. The latest estimate in the wake of last year’s Hurricane Sandy, which breached barrier islands and swept inland into the Mid-Atlantic States, is closing in on $70 billion. In the fall of 2011, the double hit of Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee caused widespread disaster and distress, even extending inland in New England. In 2005, the Gulf Coast reeled under the dual impacts of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita within a month.

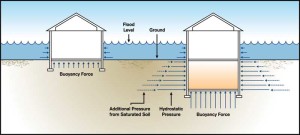

While protection of human life is always the highest priority, design/construction professionals must also be concerned with protecting immovable property in the face of flooding disasters. The power of water can overcome buildings, pushing them from their foundations, deforming and even buckling their walls. This article focuses on protecting non-residential structures housing businesses, emergency care services, government agencies, water treatment and power generation facilities, and other essential components of our lives.

Identification of regulated areas

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is the nation’s primary unifying approach to protecting lives and property from flood hazards. Created by the 1968 National Flood Disaster Protection Act, it is now under the oversight of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Although NFIP was meant to create a large national pool of policy-holders to lower flood insurance premiums, it was not long until it became evident there needed to be some kind of standards for building in floodplains to encourage wiser use of those risky areas and minimize payouts on federal flood insurance claims.

NFIP’s primary approach to reducing flood risks is through adopting minimum standards for placement and design of structures located within identified ‘one-percent annual-chance flood-hazard areas.’ It is significant the goal is to reduce, rather than eliminate, those risks. Hazards can be minimized, but not completely eliminated without simply avoiding those areas. Even outside identified floodplains, there are mounting damages as development translates to increased impervious surface within a watershed, making the area less able to absorb surface waters.

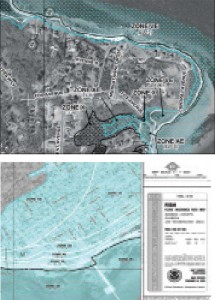

The probability of flooding of a certain extent in a particular area is described in FEMA’s Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs). Every area on this planet’s surface is subject to some probability of flooding (even if the risk is small); no area is completely immune from this hazard. Therefore FEMA’s maps indicate minimal, moderate, and Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs). It is the last of these triggering mandatory flood insurance purchase requirements when a structure in this risk area serves as collateral for a loan issued by a government-regulated lending institution.

Since the SFHA is also the basis for regulating land use in floodplains, it is sometimes referred to as the ‘base’ or ‘regulatory’ floodplain. It is shown as the darkest gray area on FIRMs and is subject to a one-percent annual chance probability of being inundated in any given year. As this probability is present each and every year, the former nomenclature of ‘100-year floods’ has been phased out due to general misunderstanding of the actual risk involved. It is possible to experience a so-called 100-year flood in consecutive years, or even multiple events in a single year.

Other risk areas are shown on FIRMs in lighter gray (i.e. moderate risk, or 0.2 percent annual chance) or white (i.e. minimal risk, or less than 0.2 percent chance of occurrence). While not as likely to experience flooding, these areas are not immune, and the resulting damages are every bit as severe as within the SFHA. Although not federally mandated, communities participating in the NFIP may proactively impose the same floodplain management and mitigation requirements in these areas as within the SFHA.