Why Red Brick Turns White: Understanding efflorescence

When this author tested the pH of masonry construction, areas without efflorescence had a pH ranging from 8 to 12; areas exhibiting efflorescence were above 12. Most paint manufacturers recommend cementitious materials have a pH of less than 12 before painting. They also recommend using an alkali-resistant primer when painting cementitious products.

Most efflorescence is temporary and consequently should be left alone. It often occurs shortly after building wash-down, and in the fall and winter when vapor transmission slows down and masonry stays damp for extended periods. Since most masonry cleaners tend to be acidic, acid rain is often a natural remover of efflorescence.

Evolutionary lesson

Beginning with calcium chloride that usually comes from lime, the following four salt compounds evolve to form efflorescence:

- calcium oxide (soluble in water);

- calcium hydroxide (soluble in water);

- calcium carbonate (insoluble in water); and

- calcium bicarbonate (soluble in water).

When calcium oxide is mixed with water, it forms calcium hydroxide; it is then carried to the surface

by normal moisture migration, mixing with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to form calcium carbonate. This is the first visible white indicator of efflorescence.

The calcium carbonate begins to react with CO2 and moisture to form calcium bicarbonate. Converting the insoluble calcium carbonate to soluble calcium bicarbonate is slower than changing soluble calcium hydroxide to calcium carbonate. Therefore, calcium carbonate accumulates on the surface as a familiar white powder. In other words:

- calcium oxide + water = calcium hydroxide

- calcium hydroxide + carbon dioxide = calcium carbonate + water

- calcium carbonate + carbon dioxide + water = calcium bicarbonate

Calcium carbonate, followed by sodium sulfate and potassium sulfate, is the most common efflorescence salt compound. After concrete is poured, mortar is laid, or plaster is applied, the hydration (i.e. hardening) process begins, and calcium hydroxide is formed.

When does efflorescence occur?

The occurrence of efflorescence is not always predictable. The soluble salt components may be present, but instead of moving to the surface, they may be carried into the wall by any form of moisture or be absorbed by groundwater.

When weather is warm or dry and humidity is low, moisture usually evaporates before it reaches the surface, leaving salt deposits internally. Conversely, when weather is wet and cold and humidity is high, evaporation can be slow (or non-existent), with conditions ripe for visible efflorescence. As a building becomes enclosed during construction, efflorescence usually disappears.

Efflorescence can occur in manufactured materials within the first 48 hours of creation or installation. It is generally associated with the initial cure during manufacture of stone, cement, and brick masonry units and construction. This produces a construction-induced moisture that moves through the cementitious structure and picks up the free salts along the way. If the moisture makes it to the surface and evaporates there before it does so internally, white salt crystals form on the exterior surface. This is sometimes referred to as ‘primary efflorescence.’

Efflorescence also occurs when moisture is induced after construction from weather, landscaping, groundwater, or leaking pipes. Considering these possible sources, it can be surmised this ‘secondary efflorescence’ tends to occur randomly—it may affect some units or portions of the structure, but not others. The chemistry and formation of both are the same; the difference is when they occur.

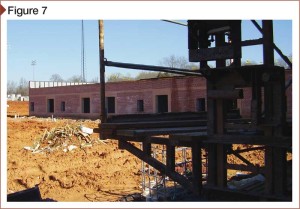

Efflorescence is sometimes called ‘new building bloom’ because it frequently appears on ‘fresh’ buildings. It can occur during, or shortly after, construction and either disappear after a brief stay or remain for a year or more. Often confused with mortar scraping from a distance, it can occur during construction (Figure 7) or in the midst of cold, damp, or rainy weather. These conditions are usually temporary and suggest the building is drying out. Cold concrete and ambient temperatures encourage efflorescence because the salts are more easily dissolved, and concrete tends to bleed more in cool weather.

Contrary to what might be expected, wet-curing concrete tends to reduce efflorescence even though more water is introduced. When concrete is kept moist during a wet cure, additional capillaries and pores are filled to form a denser matrix that resists moisture migration. Concrete with a higher slump or not properly cured often has more open pores and capillaries to promote moisture migration in all directions.

Efflorescence is least likely to occur on the south and west walls because the warm sun moves the evaporation point from the surface to deeper in the wall. Walls facing north and east tend to experience the most efflorescence because they are usually cooler, permitting the evaporation point to remain on the surface.

Any type of moisture, including humidity, supports formation of efflorescence. Consequently, it tends to increase after a rainy winter, decreases with warmer spring weather, and virtually disappears in summer. When weather is warmer or dryer and humidity is low, moisture usually evaporates before it reaches the surface, leaving salt deposits internally. Conversely, when weather is wet and cold and humidity is high, evaporation can be slow to nonexistent and conditions are ripe. When efflorescence persists, there are internal problems and an investigation should be considered.

Until the structure is dry, efflorescence occurs even on interior walls (Figure 8). Drying usually happens from the inside out, and efflorescence can occur on both sides of a wall until the drying is complete. The dark moisture spots and white efflorescence suggest that the building is drying out. It usually disappears after the building dries and ambient conditions stabilize—otherwise, there is probably more to be concerned about than efflorescence. It may be signaling something is amiss, such as persistent moisture intrusion, or inadequate drainage or drying.