Retrofitting multi-wythe masonry as a veneer assembly

By removing the mortar in the collar joint and moving the masonry veneer out 6.4 mm (1⁄4 in.), taking advantage of a cant in the concrete floor slab below, there was sufficient room for the waterproofing membrane, drainage board, and masonry ties. The depth of the new tube steel did impede into the cavity space, so the back of the brick veneer was cut to fit around the steel.

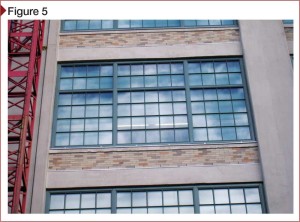

The yellow-colored brick was initially considered for salvage, but the existing mortar was so hard and well-bonded to the existing brick, it was difficult to remove in usable pieces. A new yellow and brown brick mix was used to simulate the original brick colors. The metal flashing at the masonry wall base made a slight shadow line on the concrete floor slab, but is not noticeable from grade (Figure 5).

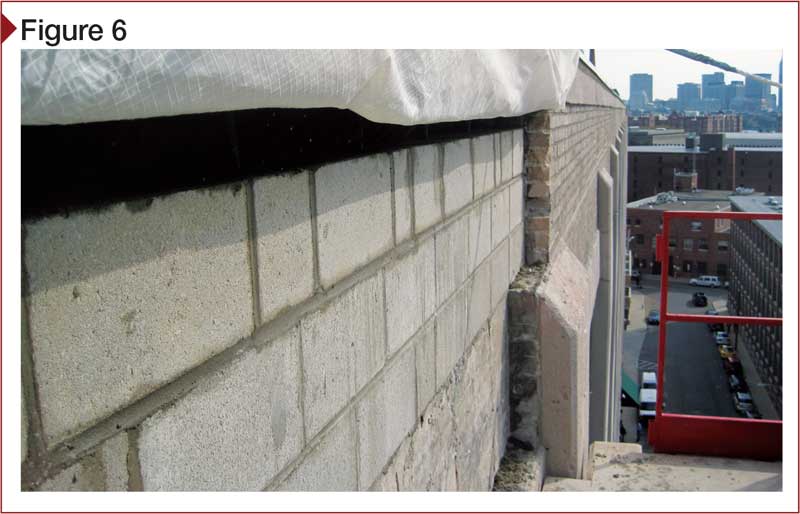

The parapet walls were completely demolished and rebuilt using a reinforced CMU backup (Figure 6). Since the parapets are built on a solid concrete roof slab, the CMU could be sized as required to meet current code loads (which was thicker than the existing wall thickness) and move the face of the blocks inward to make more room for the waterproofing and drainage space.

Demolish and rebuild

In a more unique case, a multi-wythe masonry wall was reconfigured to a veneer by demolishing the entire wall and rebuilding. This approach can be considered when the repair is to take place in a localized area and the adjacent interior space can be exposed to the exterior during demolition (such as in an attic space or unused room).

The building was constructed in 1938 in central Connecticut with its load-bearing exterior walls consisting of three wythes of brick masonry that support the steel-framed roof and floors. At the attic level, there were eight gables of varying sizes, which contained a louver or window surrounded by limestone. Not only did the masonry walls at the gables let in a lot of water during storms, but the mortar was also heavily deteriorated on both the interior and exterior.

Much of the mortar in the joints could be removed by hand, and the wall did not appear structurally sound (Figure 7). The team recommended rebuilding the gable walls, either with a new mulmulti-wythe brick masonry wall or with brick veneer walls with a reinforced CMU backup and wall waterproofing.

It was explained to the owner rebuilding the walls as a multi-wythe masonry wall would keep the exterior wall type consistent, but it would make the wall more prone to leakage and efflorescence staining due to a full collar joint of mortar. The owner decided to proceed with the veneer wall option to improve the water resistance and avoid the heavy efflorescence staining.

The general scope of work included:

- shoring the existing roof system;

- removing all three wythes of brick masonry (Figure 8);

- installing a new reinforced CMU backup wall that could support both the wind and roof loads;

- cleaning and coating the steel embedded in the masonry walls;

- installing a metal flashing with a thin drip edge at the base of the new CMU backup wall; and

- installing a new waterproofing membrane, drainage layer, masonry veneer tie, and brick veneer.

The existing wall depth (300 mm [12 in.]) provided enough room for the waterproofing membrane, drainage layer, veneer anchors, and brick veneer by ‘cheating’ the new 200-mm (8-in.) CMU back

12.7 mm (1⁄2 in.), as shown in Figure 9. After the masonry was installed and the construction complete, the thin drip edge at the base of the veneer (transition to the mass masonry below) is barely noticeable from the ground (Figure 10).

Conclusion

Building owners with multi-wythe masonry walls have options to address leakage or deteriorated masonry other than repointing and installation of clear sealers. These traditional repair approaches can help reduce leakage, but in many cases become less effective over time. Walls that lack flashing over window openings are particularly problematic.

A more effective and reliable approach is to provide for waterproofing and drainage by reconfiguring the multi-wythe wall to a veneer, air space, and inner backup wythes. While costly, this repair provides long-term performance and maintains building aesthetics.

Annemarie R. Der Ananian, PE, is a senior staff member of Simpson Gumpertz & Heger (SGH), and is part of its building technology group. She works on projects involving the investigation, design, and construction of masonry veneer and multi-wythe masonry for both commercial and educational buildings. Der Ananian can be contacted via e-mail at arderananian@sgh.com.