The ins and outs of revolving doors

by Glen Tracy

The built environment is an energy-guzzler. The U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) states in this country alone, buildings account for 41 percent of energy use, 73 percent of electricity consumption and 38 percent of all CO2 emissions, and 13.6 percent potable water consumption. Globally, buildings use 40 percent of raw materials, or about 3 billion tons annually. Fortunately, the type of doors we select can have a big impact on a building’s energy profile.

Revolving doors can be up to eight times more energy-efficient than their hinged counterparts—all while allowing large numbers of people to pass in and out, boosting security, and adding architectural interest. In other words, not only can revolving doors efficiently handle bi-directional pedestrian traffic and reduce energy costs by maintaining an airlock, but they can also improve comfort for building occupants and offer more usable space at entrances compared to vestibules.

This article discusses the green features of revolving doors and considers design elements as they relate to user comfort and safety. It also offers a checklist of must-dos in properly specifying a revolving door for a given project.

ABCs of revolving doors

A revolving door generally consists of door wings that hang on a central shaft and rotate around a vertical axis within a cylindrical enclosure called a drum. There are usually two, three, or four wings that typically incorporate glass. The opening of the drum enclosure is referred to as the throat.

Manual revolving doors rotate with push-bars, causing all wings to move. Large-diameter revolving doors use a motor to rotate automatically, and can accommodate strollers, wheelchairs, and wheeled luggage. A speed control (or ‘governor’) mounted in either the ceiling or floor prevents the door moving at an unsafe speed.

Automatic revolving doors are powered above or below the central shaft, or along the perimeter. Sensors in the door wings and the enclosure frame ensure the speed with which the door revolves is limited. Other sensors can prevent or minimize the force of impact of the door wing on users.

Revolving doors were invented in Philadelphia in 1888 by Theophilus Van Kannel to reduce air infiltration. His company’s original motto was, “Always open, always closed”—that is, always open to people, always closed to the elements.

A basic understanding of the way air behaves in a building sheds light on the benefits of revolving doors. Generally speaking, per the stack effect, air flows in and out of a building because of differences in air pressure and humidity. In the winter, heated air rises toward the top of a building and as long as there are any openings on the ground floor, cold air rushes in to replace the heated air. The opposite happens in the summer.

Energy saved by revolving doors

In 2006, a team of graduate students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) conducted an analysis of door use in one building on campus, where they found just 23 percent of visitors used the revolving doors. According to MIT’s calculations, the swinging door allowed as much as eight times more air to pass through the building than the revolving door.

According to the subsequent April 2009 MIT Tech Talk publication:

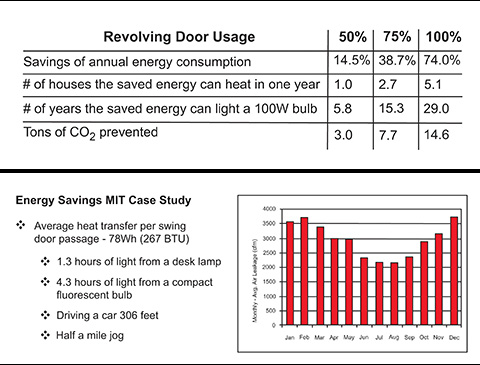

students indicated that if everyone were to use the revolving doors in this one building alone, MIT would save almost $7,500 in natural gas a year. That’s enough to heat five houses over the same timeframe, and it also adds up to nearly 15 tons of CO2.

The MIT findings on how revolving door usage affects energy consumption are shown in Figure 1.