Protecting those inside: Specifying blast hazard-mitigating windows

by Tom Mifflin

Exposed to the extreme pressure released by an explosive mass, elements of the window or curtain wall assembly work together to withstand the blast load and dissipate its energy. Laminated glass takes the brunt of the blast force, the framing connections and glass bites work together to keep the lites in their frames, the mullions and sashes adequately deflect to handle the assembly’s changing shape, and window hardware transfers load to perimeter framing.

As the blast load is transferred from exterior to interior, the window or curtain wall anchorage must help ensure the most comprehensive protection. Flexibility is key—too many anchors make the assembly overly stiff, and add unnecessary time and cost to the installation schedule. The type and number of anchors depend primarily on the substrate and its robustness. Ultimately, residual blast energy is imparted to the building structure itself.

Understanding how these assemblies work is critical for specifiers and design professionals working on high-profile architectural structures and iconic destinations, along with high-value institutions, such as banking and financial centers, transportation networks, utilities, water supply systems, and emergency and medical facilities. However, it is also especially important for public-sector projects.

In a response to the terrorist attacks of the past 20 years, security policies at all levels of government have been developed and continue to be updated. These policies enhance protection in not just owner-occupied facilities, but also in domestic real estate leased by federal, state, and local governments, as well as U.S. military services and the intelligence community, law enforcement, fire, rescue, and first responders.

Windows for military facilities

Blast hazard mitigation requirements for planning, design, construction, and modernization of many U.S. military facilities are defined in the Department of Defense (DoD) Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC) 4-010-01, “Minimum Anti-terrorism Standards for Buildings,” 9 February 2012, Change 1, 1 October 2013 (referred to hereinafter as UFC 2013). They can include barracks and billeting, family housing, office structures, armories, readiness centers, and child development centers (on and off military bases).

UFC 2013 Appendix B Standard 10 covers windows, curtain walls, and skylights. Requirements in previous versions of this standard were generally based on capacity of wall construction for “conventional construction standoff distance,” and allowed pre-engineered designs to comply based on limited analysis and even standard product testing.

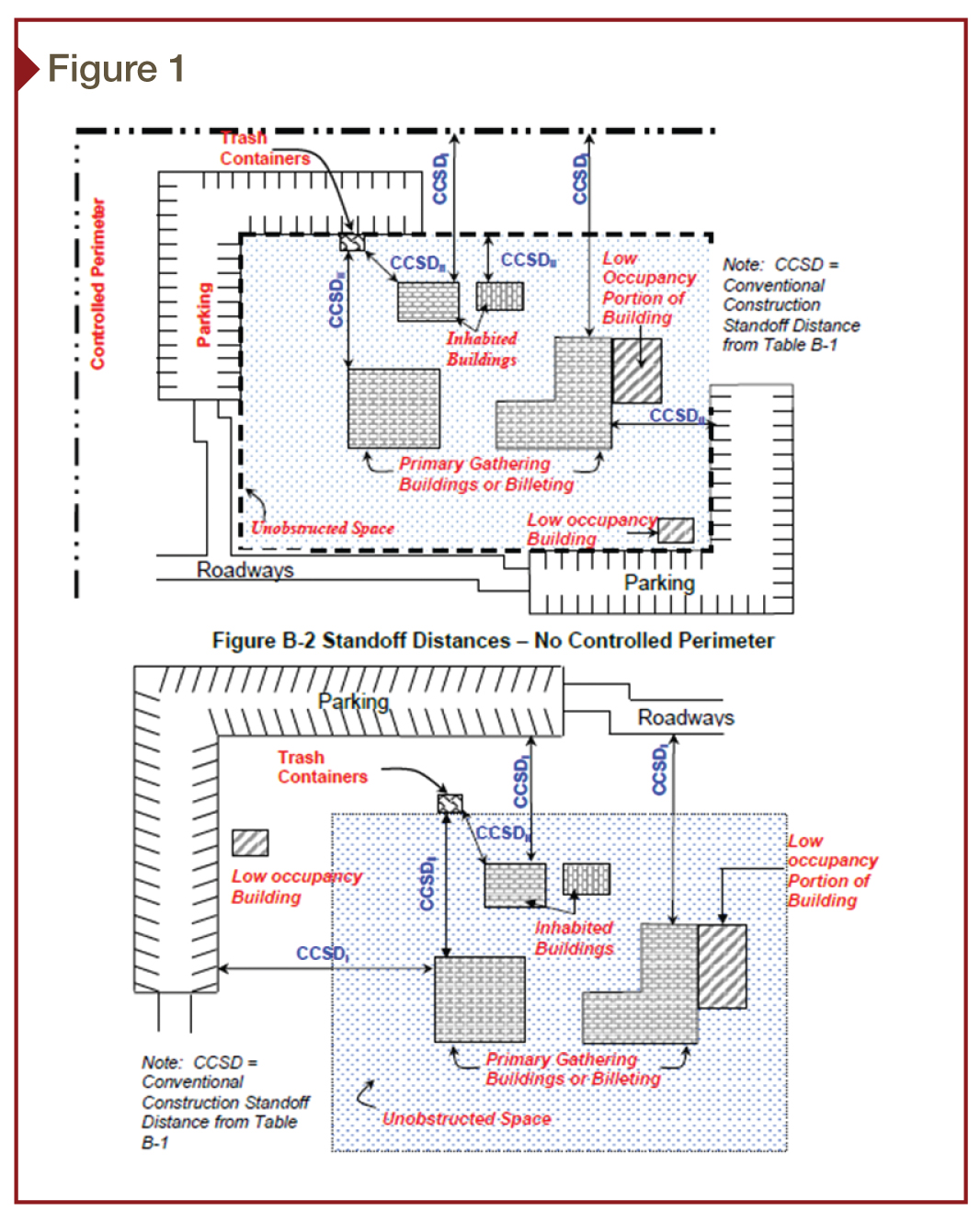

The UFC 2013 standard requires window and curtain wall designers and specifiers to consider certain parameters of the specific building’s threat assessment—standoff distance and charge weight—as well as protection level. In simple terms, design must be based on the project-specific site plan, perimeter control fences, and checkpoints shown schematically in Figure 1, as well as acceptable intrusion of glazing fragments into perimeter areas of the occupied space. Unlike previous versions, one-size-fits-all pre-tested, standard blast windows seldom meet UFC 2013 requirements.

The current version of the standard allows for value-engineering of blast hazard-mitigating windows and curtain wall in the same project, based on exposure. Relative to fenestration, UFC 2013 provides the following rationale for changes to the standard:

– To reduce misunderstandings of some of its provisions.

– To address situations not previously addressed by the standards.

– To improve consistency of interpretation.

– To reduce redundancy or inconsistency with other UFCs that were not available at the time of the previous revision.

– To eliminate standards or recommendations that were unnecessary or that had been superseded by other UFCs.

– To incorporate information based on new studies and research or new or revised national standards.

– Reduced costs of window systems and of supporting structural elements due to changes in Standard 10 on windows and skylights.

– Added warnings throughout the document that for some wall types the conventional construction standoff distances will require window and door construction that is significantly heavier and more expensive than windows and doors designed at the conventional construction standoff distances in previous versions of these standards.

In general, many windows tested to previous versions of the standard have been found to be adequate when project-specific standoff distance is greater than 13.1 m (43 ft) for Charge Weight I, or 7 m (23 ft) for Charge Weight II for a “Low” level of protection. For any given project, these generalizations may or may not apply. Design parameters for peak pressure in kPa (psi) and impulse in kPa.msec (psi.msec) vary widely between projects and even between elevations within a building.

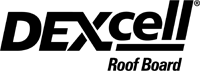

As shown in Figure 2, peak positive pressure occurs almost instantaneously after the arrival of the shockwave, dissipating in milliseconds to the negative phase rebound load. The area under the positive pressure-time curve is defined as the positive phase impulse—a measure of the blast energy imparted to the glazing.