Specifying windows for behavioral healthcare projects

courtesy Apogee Architectural Metals

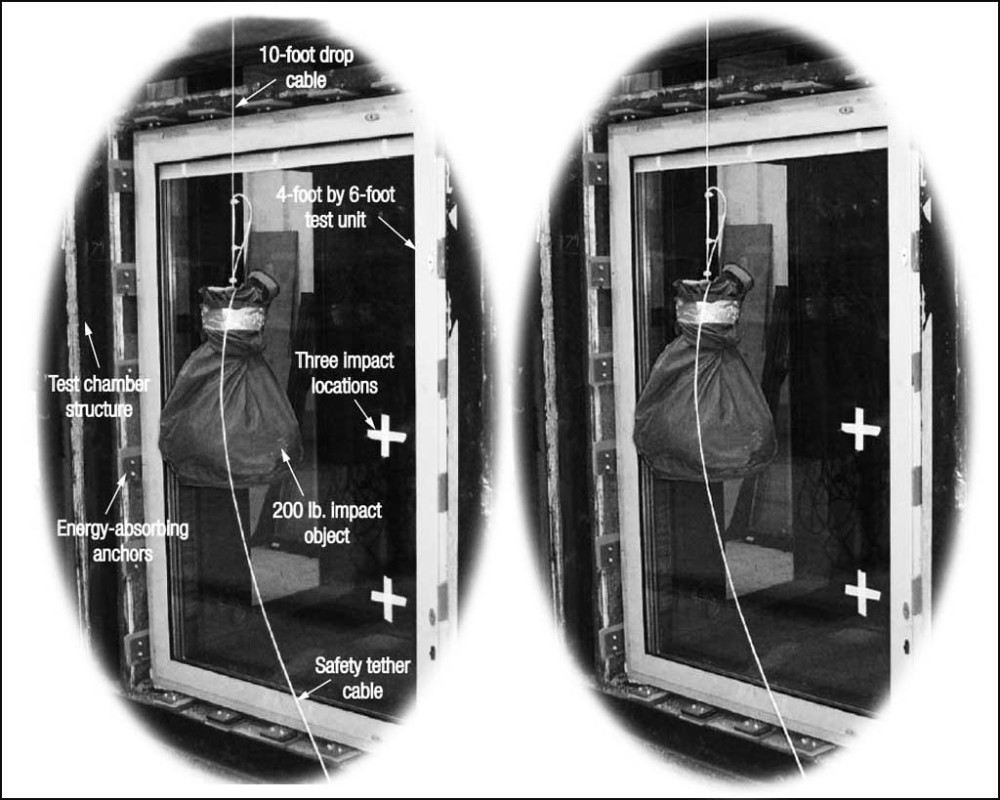

As with selection criteria, additional site-specific pass/fail criteria may apply to drop-tested behavioral windows. Depending on the furnishings and equipment accessible to the patients, simulation of physical attack with objects may be advisable. Exterior laminated glass should be used at windows at grade, courtyards, or porches with supervised patient access. Codes and standards vary widely by jurisdiction, so there should be consultation with onsite medical and security staff to determine appropriate resistance and necessary security.

It can be challenging to select products and materials that help create a pleasing environment, while enhancing the treatment process and maximizing safety. Selected resources offering guidance for material selection for inpatient behavioral units:

- Design Guide for Inpatient Mental Health & Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program Facilities, published by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

- The Design Guide for the Built Environment of Behavioral Health Facilities, distributed by the National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems (NAPHS)

- Design Guide of Behavioral Health Crisis Units, published by the Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI)

- Patient Safety Standards, Materials and Systems Guidelines, recommended by the New York State Office of Mental Health, developed in association with Architecture Plus of Troy, New York

These documents help examine the environmental aspects that can have a significant impact on patient safety and healing. The products they recommend have been evaluated to help lower patient risk.

Daylighting: enhance healing environments

“Views to the exterior that offer a positive distraction as well as a time reference can steady an individual experiencing discomfort, disorientation, and stress,” notes FGI’s Design Guide of Behavioral Health Crisis Units. In many new buildings, the design team attempts to maintain high visible light transmittance (VLT or VT) to ‘connect’ the occupants to the outside, provide views, and exploit natural daylighting. It is not only the amount of natural light that is important to building occupants, but also its quality, spectral composition, contrast, variability, and directionality.

Specifying tall windows helps maximize light penetration. Clerestories can be used to increase the effective height of transom lites without increasing window-to-wall ratio (WWR). Even relatively low WWR provides more than ample natural daylighting, when properly oriented and directed.

Within the programmatic limitations of a healthcare occupancy, natural daylighting is most energy-efficient if artificial lighting is automatically controlled. Photosensitive controllers and occupancy sensors can be used to dim or extinguish indoor lights when unnecessary. Artificial lighting accounts for about 40 percent of the energy used in a typical commercial building and generates at least three Watts of heat for each Watt of visible light.

Designers are encouraged to consider the concept of effective aperture (EA), the product of VT and WWR. Essentially, EA is the light-admitting potential of a glazing system, and determined by multiplying the WWR by the VLT. This can be useful when assessing the relationship between visible light and window size. One should start with an EA of about 0.3 on the north and south elevation, minimizing glazing on the east and west elevations whenever possible.

Unless “downward” view is important, vision glass should be eliminated below sill height to reduce solar heat gain that carries no useful daylight. Generally, the window area should be no different in naturally lit buildings than other conventionally lit ones.

In addition to sunlight and views of nature, high-performance window systems can assist with energy efficiency. Thermally broken frames with triple glazing, along with a broad selection of exterior glass options, provide enhanced energy performance and condensation resistance.

courtesy Apogee Architectural Metals

Integral between-glass blinds reduce solar heat gain, offer privacy control without the potential dangers of exposed cords, and minimize the need for maintenance. The tilting of the slats can be keyed for staff operation or to allow patient control with a low-profile ligature-resistant control knob. Raise-lower controls for between-glass blinds are usually limited to custodial access. Controlling raise-lower access allows for uniform blind placement vertically and a resulting consistent exterior appearance.

Many areas in hospitals are required to maintain high relative humidity (RH), as well as prescribed positive or negative internal pressure, for therapeutic reasons or contagion control. Condensation occurs on any interior surface falling below the dewpoint temperature (Tdp) of interior ambient air. Tdp is dependent on temperature and RH, as warm air can hold more moisture than cold air. Condensation can be unsightly, unsanitary, and damaging to adjacent building materials over long periods. For these reasons, condensation should be assessed for both frame and glass in applications where high humidity is maintained.

Finite element computer models and the condensation resistance factor (CRF) test results using AAMA 1503, Voluntary Test Method for Thermal Transmittance and Condensation Resistance of Windows, Doors, and Glazed Wall Sections, can be useful in comparing products or as a basis for performance specifications. The design professional should exercise caution when using these tools to predict or prevent condensation on installed products. Field condensation on interior surfaces is affected by many variables, including:

- component thermal performance;

- thermal mass of surrounding materials;

- interior trim coverage;

- air flow conditions;

- weather; and

- mechanical system design.

CRF applies only to pre-defined configurations under controlled and steady-state laboratory conditions; it assumes some condensation is acceptable under the severest of winter conditions.

Air infiltration through windows and walls is also important to total building energy performance. It not only takes “sensible” energy to heat or cool infiltrating air, but also may require “latent” energy to remove undesirable humidity. Air infiltration performance is usually considered separately from other thermal performance characteristics.